University

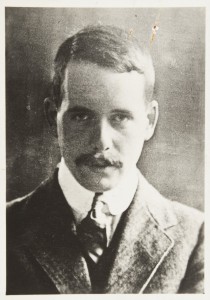

After finishing at Eton, Harry returned to Oxford where he studied for a four-year natural sciences degree at Trinity College. Harry held the Millard Science Scholarship and chose to specialise in physics.

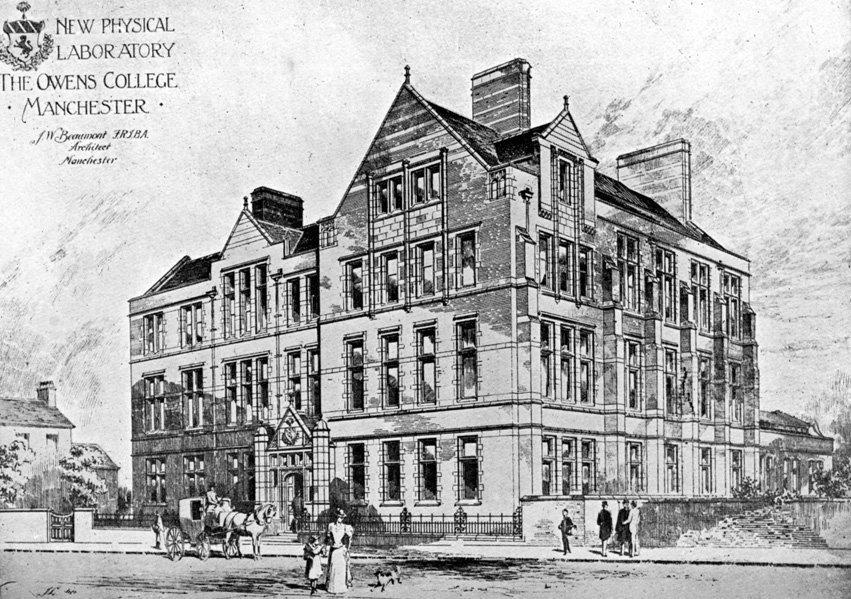

Upon completing his degree at Oxford, Harry immediately left for Manchester to work under the leading physicist Sir Ernest Rutherford. Manchester and the Rutherford research team were at the ‘cutting edge’ of physics research, particularly in comparison to the more traditional Oxford.

The significance of Harry’s research in Manchester, as well as at Oxford where he returned in 1913, was quickly appreciated. Despite a research career of only 40 months, by 1914 he was already contemplating his next move and applying for professorships in physics. Although only in his mid-twenties he was able to gather support from the most distinguished physicists of the period.

Below is an animation of Harry’s X-ray Spectrometer. This 5 minute animation provides a detailed visual explanation and simulation of Moseley’s ground-breaking scientific experiment. This animation by Martin Wolff is a collaboration between the Museum of the History of Science (MHS) and the Hochschule für Technik und Wirtschaft (HTW) Dresden.

Student Life

Harry was awarded a scholarship by Trinity College, Oxford and arrived in October 1906. His arrival is recorded in Trinity College’s Admissions Register on 12 October 1906, entering as a Millard Scholar. Of the twelve men listed on the same page as Harry in the Register, four were killed in the First World War. One of those who survived was German.

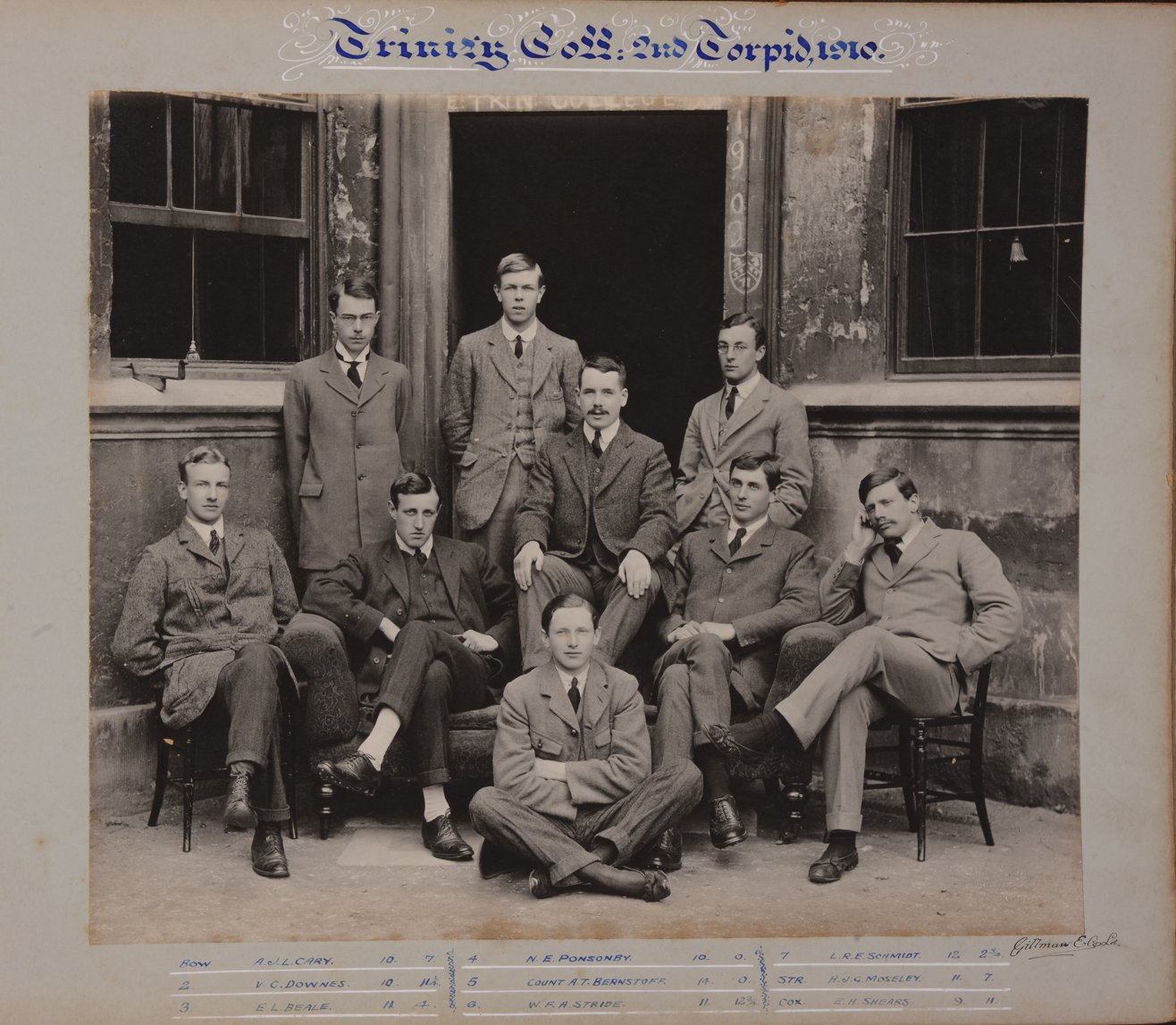

Harry’s real enthusiasm was for science, and physics in particular. But he took part in traditional student activities such as rowing, where the international character of the student experience continued beyond the curriculum. Harry appears in five crew photographs from the College’s Boat Club. In the “Torpid” races of 1910 there were two German members of Harry’s boat. Earlier he had rowed in a smaller pairs boat.

The exhibition featured a quarter-pint pewter pot commemorating a scratch race in 1907 where Harry was one of two English oarsman coxed by a German Rhodes Scholar.

Harry’s progress in science during his undergraduate degree was reviewed every term in the Senior Tutor’s “Collections” notebook. In the autumn of 1908 he was described as “very erratic & rather untidy but works very hard.” A year later the outlook was more positive: “much more methodical: improving steadily”. The results of more formal examinations were also recorded. The Senior Tutor’s Register lists Harry’s success in Mathematics “Moderations” during the summer term of 1908.

Exam Fever

The heat here has been insupportable; I have therefore of course spoiled all my chances … Two elementary papers today, not great success. I was fighting inefficiently against time. The heat is overpowering, and an owl squawked all night in the garden and kept me awake.

Letter from Harry to his mother, June 1910, during final examinations at Oxford

Beyond his required studies, Harry was an active member of Oxford’s informal scientific societies. Small groups of undergraduates would meet to review and discuss recent developments, with support from a few more senior university scientists.

Harry was an active participant in the Alembic Club, a mostly undergraduate scientific society whose discussions centred around chemistry. The tone was not always serious: although founded just a few years earlier in 1901, the club’s Minute Book 1 is titled “Ye Booke of Ye O.U. Alembicke Clubbe”. A highlight of each year was a lavish dinner, and Harry and his fellow students signed a menu together in 1908.

The club’s programme was printed each term and Harry appears both as a speaker and as an office holder. When he returned from Manchester to Oxford he spoke again in 1914, bringing news of recent ‘cutting edge’ research on radioactivity at Manchester.

FRONTLINE PHYSICS

Harry moved to Manchester after graduating in 1910 and began teaching and research. He joined a team at the forefront of physics, working under Ernest Rutherford.

Ernest Rutherford (right) and Hans Geiger (of Geiger tube fame, left) in the Manchester physics laboratory, 1912.

Harry’s most important research was begun in Manchester and continued when he moved back to Oxford in late 1913. By studying the X-rays produced from different elements, he established a new physical basis for ordering the periodic table used by chemists.

Midnight Oil

Moseley was without exception or exaggeration the most brilliant man – and the hardest worker I have ever met. There were of course no regular meals, and work often went on for most of the night. Indeed one of Moseley’s expertises was the knowledge of where one could get a meal in Manchester at 3 o’clock in the Morning.

Charles Galton Darwin in a 1916 obituary of Harry.

Harry’s most important work was conducted with a complex experimental setup, requiring ingenuity in design and determination in operation. Several pieces of connected apparatus were used.

An induction coil supplied high voltage to an X-ray tube, which was evacuated with a powerful Gaede mercury vacuum pump. Within the tube, electrons were fired at a sample of a chemical element, creating X-rays specific to that element. Having to make and break a vacuum between each experimental run slowed down the work, and increased the risk of leaks. To increase the speed of the experiment, Harry ingeniously used a trolley on a set of rails to present a succession of elements without breaking the vacuum. Acquired from many sources, the elements were identified and stored in envelopes.

The X-rays were made parallel by passing through a slit and into a cylindrical chamber, the spectrometer. In the centre of the spectrometer they struck and were deflected by a large mounted crystal of potassium ferrocyanide. Finally, the most characteristic X-rays were recorded photographically. For Harry, the crucial information was the angle of the X-rays, so the photographic plate holder sits in a track marked with degrees around the perimeter of the spectrometer. Given the significance of the results, the photographs are very unassuming.

[ Next: Military Training ]