A guest blog post by Gavin Hannah, Summer Fields, Oxford, Editor Summer Fields, the First 150 Years (Third Millennium, 2014).

Early in September 1897, the ten-year-old Henry Gwyn Jeffreys Moseley, generally known as ‘Harry’, arrived at his prep school, Summer Fields, Oxford, as one of a batch of twenty-eight new boys. Founded in 1864, by the energetic and progressive Gertrude Maclaren, initially to teach Greek and Latin to her nine-year-old daughter, the school had soon attracted other pupils and the necessary staff to teach them. Thus, when Harry began his studies Summer Fields was a thriving institution numbering about 120 boys, most of whom were boarders. By that time also, it had established a formidable reputation for the rigour of its teaching, particularly of Classics. Indeed, Summer Fields was renowned for its success in preparing its pupils for the Eton Scholarships. In 1905 for example, no fewer than 19 of the 70 scholars in College at Eton, were Old Summerfieldians.

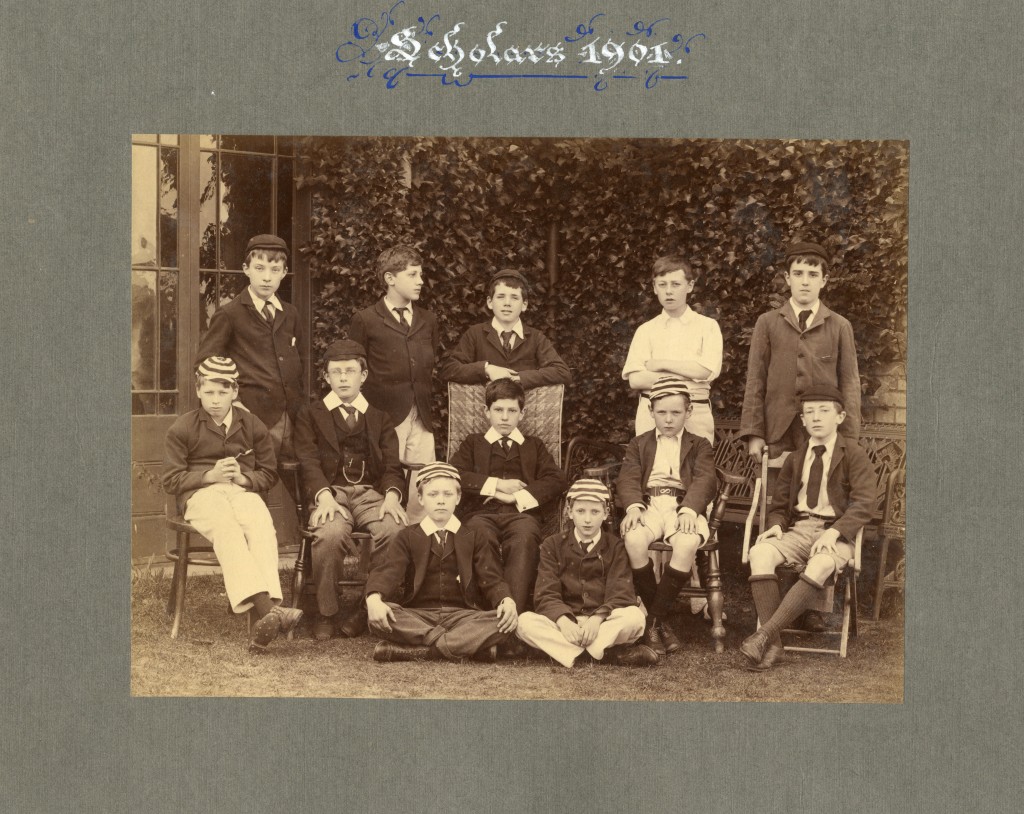

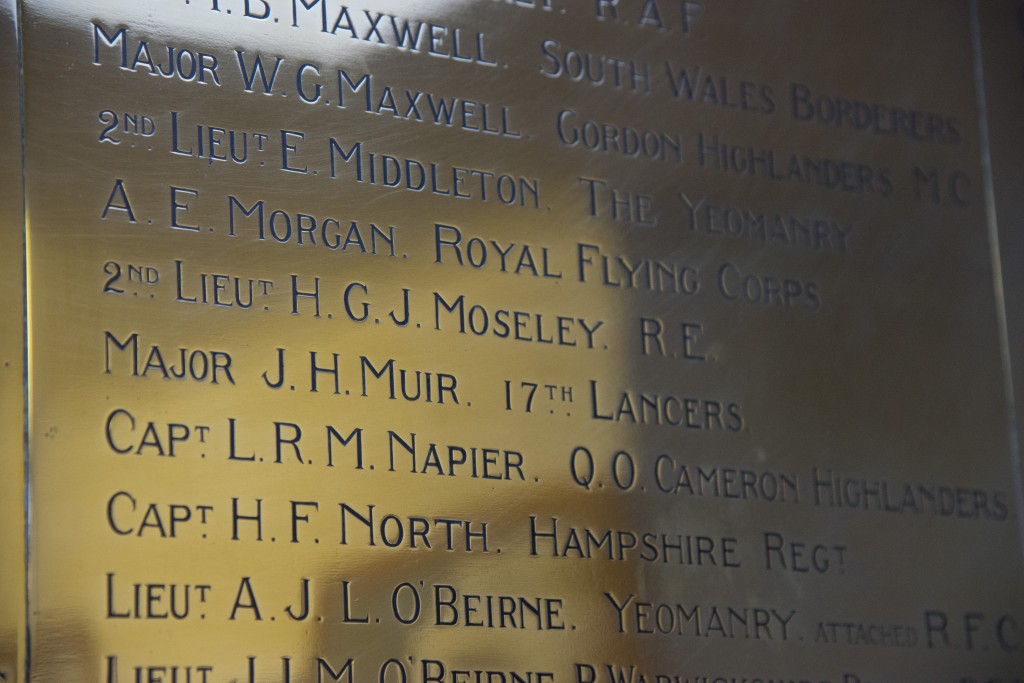

So began an educational journey that took Harry Moseley on to Eton, as a Scholar, in 1901, then to Trinity College, Oxford (also as a Scholar) followed by the Victoria University of Manchester for research under Ernest Rutherford. Moseley then returned to Oxford in 1913 to continue his independent scientific investigations which eventually led to the formulation of Moseley’s Law and a reassessment of the Periodic Table. At the outbreak of the First World War, Moseley forsook the Groves of Academe for the Royal Engineers and while serving as a communications officer in the Gallipoli campaign, he was killed in action on 10 August 1915. Of note is the fact that the Great War claimed the lives of ten of his peers, many of them friends, who had started their Summer Fields careers alongside him.

Thus perished one of this country’s greatest scientific minds; nipped in the bud. Indeed, Rutherford speculated that Moseley might have been awarded a Nobel Prize for physics had his life not been cut short. It is said that he accomplished in a brief but brilliant career of just forty months, what few achieve in a lifetime of research and study.

What then may be said of Harry’s time at Summer Fields? What do we know of that world he entered, centred on an early nineteenth-century villa tucked away in 70 acres of fields at the end of Summerfield Road in Summertown? What of those who taught him? What of Harry’s progress and attainment at the school? Was it from Summer Fields that his passion for science was first stimulated and then nurtured?

Although founded by a woman, Summer Fields was essentially a male world, and for Harry, feminine influence was sadly lacking. The only women he might have met, apart from the kitchen maids (as they were termed), laundry girls and cleaning staff, were Miss Sarah ‘Sally’ Williams, who taught some of the junior boys, Nurse Bright, Miss Lilwall Peirce, the school Matron, Mrs Paine, the Housekeeper and Mabel Williams, the Headmaster’s wife.

However, during his first days Harry would have definitely encountered the redoubtable Miss Wheeler, who taught music. As a new boy, he had to parade before her for an aural test. This consisted of placing one finger on piano keys in an attempt to pick out the melody of the National Anthem. To those with no musical ear came the firm command, ‘You will not learn music.’ Unfortunately, we do not know whether or not Harry was a recipient of this stern rebuke!

Summer Fields school photograph of ‘A Regular Fix’ cast in costume including Moseley in centre back (1900).

In 1897 there were twelve masters including the Headmaster, Dr Williams. Of these, nine were Oxford men, not surprising considering the proximity of the university to the school. Cambridge had only one representative. The two others were graduates of Trinity College, Dublin.

Not all of them taught Harry, but, around the school, he would have encountered such characters as J. F. ‘Crab’ Crofts. Tall, lean, bearded, rather yellow of complexion, he did not suffer fools gladly but was at heart a kindly man. Crofts also hated any rounded back and would stride swiftly and alarmingly along the benches on which boys were apt to lounge, driving into any arched vertebrae a bony-knuckled fist and chanting through clenched teach, ‘Creatures! Creatures! – sit up, sit up!’

Another of Harry’s masters was F. H. ‘Ping-Pong’ Penny from All Souls. Penny was a lugubrious, wraith-like figure, fond of putting on school plays. Care was needed with him as he had a strange habit of walking down the corridors with a clenched fist outstretched in front of him for boys to walk into if they ran round corners!

Harry received his French instruction from G. W. ‘Bam’ Evans. ‘Bam’ was an Irishman with a little moustache and beard who taught his pupils in a broad Dublin accent and enjoyed bowling when playing cricket. Affable and learned in an odd, haphazard way, he had an excellent knowledge of both English as well as French literature and was a fast reader. He once boasted that he had read the whole of Thackeray’s works during one Easter holiday and the whole of Dickens in another. ‘Bam’ had a peculiar habit of coughing with his tongue out and, when speaking, he thrust his face forward until it was within inches of the listener. He lived in Newton, one of the large villas on the school site where, as a keen gardener, he tended the roses with both affection and skill.

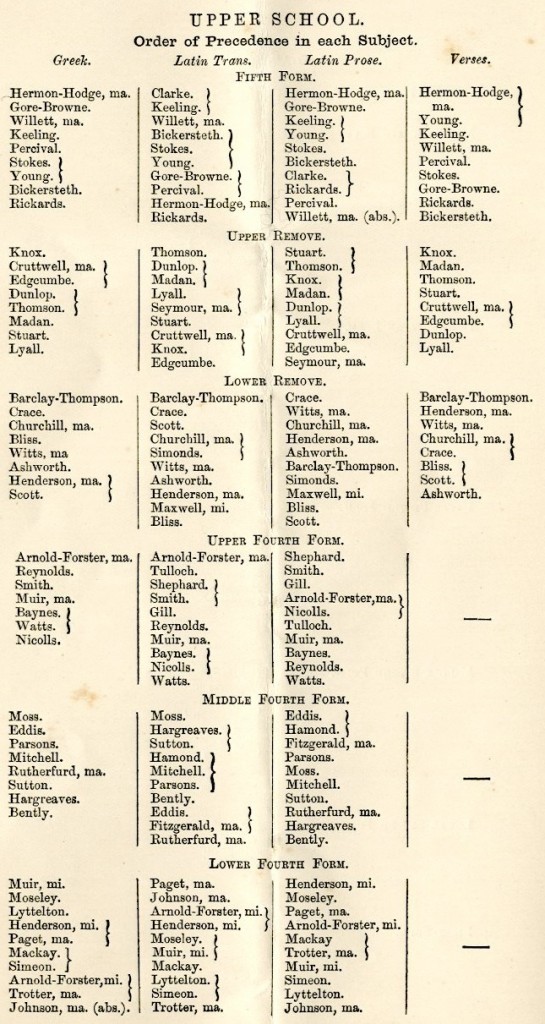

Summer Fields Upper Schools register for 1899. Harry is listed the Lower Fourth Form and is in the top three in all subjects.

During his penultimate year, in a Form called the Upper Remove, Harry studied Latin and Greek grammar, as well as the easier plays of Euripides, under the Rev. Edward Hugh ‘Bear’ Alington. Brought up in a strict Victorian parsonage, ‘Bear’ insisted on the highest standards of both discipline and scholarship. He was also a fine sportsman having won a soccer Blue at Oxford. Thus, he organized all the school games. Alington was a firm believer in the idea that effort should be rewarded and he gave a silver pencil case to every boy in his Form who subsequently won a scholarship, so it is highly likely that Harry Moseley boasted one such trophy.

In Fifth Form, Harry was successfully prepared for his Eton Scholarship during his final terms by the renowned Dr Williams, Headmaster 1896-1918. ‘Doctor’, as he was known, was a fine Classical and Biblical scholar – he held an Oxford DD. The Doctor was another austere character who insisted upon the highest standards of scholarship in all aspects of Latin and Greek literature and Grammar. Under him, Harry studied his copy of Borva Notes, a vade mecum of Classical grammar for generations of Summerfieldians. If tradition were followed, in 1901 Harry was taken to Eton by the Doctor along with the other scholarship candidates. The boys wore straw hats with the school ribbon in the colour of Brasenose (the Doctor’s old college). They stayed at the White Hart in Windsor, invariably cramming in some last-minute revision over breakfast at which fish was always served in order to stimulate the brain. They were ‘trained to the hour’, recalls one of Harry’s peers and ‘full of the joy of battle’. Despite the strictness and general austerity of the prevailing Summer Fields regime which Harry endured, one famous Old Summerfieldian later remarked that, ‘Dr Williams and his staff gave us a very happy and encouraging start to our young lives’.

From the surviving Form Lists it is possible to trace some aspects of Harry’s progress and attainment throughout his school career. The Form hierarchy at Summer Fields, which occasionally changed, looks complicated to the modern eye with strange names such as ‘Shells’ and ‘Removes’. In Harry’s day, there were fourteen Forms, ranging from the First Forms for the youngest pupils, to Fifth Form for the potential scholars. Within each Form boys were ranked in order of success in Latin. There was room for movement between Forms (both up and down) during the course of the academic year. The school was further set from top to bottom in nine academic Divisions for other examinable subjects.

The curriculum facing Harry in 1898 (his second year) consisted of Classics (Latin and Greek, with both prose and elementary verse composition), maths, English, French, Divinity, history, geography, dictation, spelling, music, drawing, carpentry, gymnastics, athletics and swimming. Opportunities existed for drama, but there is no mention of science!

As a New Boy, in 1897, Harry was placed in the Upper Second Form. This suggests that his academic ability had already been recognized as there were three Forms below this to which new boys could be assigned. By May 1899, having moved through the Third Forms, and skipped the ‘Shells’, Harry appears in the Lower Fourth. From the Lists, it seems that he was no mean Classicist as he is ranked second in a Form of ten boys. Indeed at the end of that Summer Term, Harry was awarded the Classics Prize; ‘Bear’ Alington, the adjudicator, claiming that the overall standard of Harry’s Latin grammar was higher than his skills in pose composition. At this stage, he was better at maths than English; placed in the 2nd Division for maths, but only the 5th for English.

In September 1899, Harry was significantly promoted to the Lower Remove. Again in ‘Latin Order’, he is listed as 4th in the class of ten. Still in the 2nd Division for maths, he has now moved up the 3rd for English.

By 1901, his final year, Harry was a member of Fifth Form – the group of potential scholars. Fifth Form was usually constituted as a class only in the January of the relevant scholarship year. Thus, Harry probably spent the Lent, Summer and Michaelmas Terms of 1900 in Upper Remove before his final elevation to the ranks of the school’s academic élite.

Classical teaching was the most efficient in the school and very effective in securing Eton scholarships. Everything on the work side was geared towards them. The teaching approach was skilfully devised to prepare the boys for examination conditions. For most lessons in his two final years, Harry perched on his stool in a half circle around the desks respectively of ‘Bear’ Alington and Dr Williams. He and his peers attended extra evening sessions laid on in the Doctor’s private quarters, at which the boys received cake as an incentive to master their irregular Greek and Latin verbs. Harry was trained as thoroughly as a racehorse. Even at table, after meals, the study of Latin and Greek grammar was the order of the day for potential scholars.

All the Doctor’s drive and encouragement paid off and the result was academic success. Harry won the 5th King’s Scholarship to Eton in a year when Summer Fields achieved a total of seven Eton awards, ‘although not the First KS which we have successfully held against all-comers for the last five years’. Harry Moseley had done well. His own Classics papers were described as being ‘of a very high standard’ by the Eton examiners. In his final Prize Giving Harry received the top award for mathematics and the ‘Supplementary Prize’ for Classics in Fifth Form. This latter award, although a kind of proxime accessit, strongly suggests, when assessed against Sumer Fields standards in Classics at that time, that Harry was truly a fine Latin and Greek scholar. That his mind was clear and logical is suggested again by his success in mathematics.

As might be expected in a school founded by a woman whose husband, Archibald Maclaren, ran the Oxford Gymnasium and wrote physical training manuals for the Army, the notion of health and fitness achieved through sport was highly valued at Summer Fields. Unfortunately, Harry Moseley does not feature in this aspect of the school. His name never graces any of the team lists for the major games, such as cricket and football, although he did enjoy a little golf. On the playing fields, the well-organized games and athletics, included the amusing ‘Torpids’ in which the boys ran bumping races over low hurdles wearing in their caps coloured ribbons of either Oxford or Cambridge colleges of their choice. Most boys naturally chose Oxford colleges and a popular college could have a large number of ‘boats’ on the ‘river’. None of this appealed to Harry and it is even recorded that he ‘lost his place in Torpids’ during the Lent Term of 1899. Later, of course, he rowed he rowed in real Torpids for Trinity College when at Oxford.

Harry’s most notable athletic achievement seems to have been to pass his swimming test during the summer of 1900. This he achieved in the muddy ‘deep end’ bathing place on the Cherwell where the river flows alongside the school fields. He had to swim to the far bank and back then tread water, hands held up aloft, while his feet pedalled. The whole operation was directed from the bank by the Doctor issuing his commands through a megaphone. Fortunately for Harry, the final verdict was, ‘Passed!’, rather than, ‘oh dear, not yet’, that reserved for those who sank!

So, how did Moseley’s passion for science begin and what was the role of Summer Fields in developing it? Clearly, Harry Moseley was an intelligent and observant boy and his innate interest in the natural world around him may have sparked the desire to learn more about how it worked. There was a strong family influence, too. His father was Linacre professor of Anatomy at Oxford and both his grandfathers were Fellows of the Royal Society. It would have been surprising had there not been scientific conversations at home.

Sadly for Summer Fields, there is little that the school can take credit for in this respect. Science was not highly regarded during Harry’s days there. It was barely part of the curriculum and such material as was taught was rudimentary, to say the least, when compared to the advanced standards of Classics. It is true that there was an unhurried trend towards the observation of scientific phenomena through controlled experiments. And science became especially appealing to inquisitive boys when a young woman arrived to teach biology and told a group of embarrassed, but attentive, twelve-year-olds the facts of life, with diagrams. Sadly she lasted less than a term! But such developments came long after Moseley had left.

If Harry were a boy at Summer Fields in 2015, he would enjoy a very high standard of science teaching in a dedicated, well-equipped science centre with specific laboratories for chemistry, physics and biology, as well as a state-of-the art ICT suite.

It is most likely that Harry’s science began to flourish at Eton in a school with better facilities and generally more science on the curriculum. There, his aptitude for science began to bear fruit and in December 1905, he received two ‘Natural Science’ prizes for chemistry and physics, some of the earliest scientific honours to come his way.

However, if intellectual discipline, hard work, perceptiveness, inquisitiveness, observation, rigorous analysis, critical thinking and clear expression, both orally and on paper, are considered to be some of the prerequisites of a good scientist, Summer Fields may be said to have honed these skills in Harry’s early days.

In 1926, the four Summer Fields ‘Leagues’, modelled on the public-school House system, were first introduced to give the boys some esprit de corps. ‘Moseley’ was chosen as the name for one of them. Its colour is blue. To-day, the Leagues serve as organizational units for competitions of all kinds, both academic and sporting, and Moseley comprises roughly one quarter of the school population. Harry Moseley’s name is daily on the lips of many boys and, a century after his death, he thus lives on.

Summer Fields: the Interior of the Macmillan Hall and Music Centre, formerly the gymnasium during Harry’s time at the school. Photograph by Elizabeth Bruton.

Summer Fields: The modern library, formerly the dining room during Harry’s time at the school. Photograph by Elizabeth Bruton.