|

Much seventeenth-century theology took the form of commentary on the text of scripture, which was generally believed to be the inspired word of God. For Protestants especially, the purpose was to bring out the literal meaning of the text, and to situate particular passages within the larger narrative framework of the Bible, often by providing doctrinal and historical context or by the use of cross-references. The Old and New Testaments were thought to constitute a single story, which was historically accurate and which taught clear lessons for moral practice. Exemplars drawn from the Bible provided models for contemporary human activity, in part by embodying types of ideal behaviour. Thus the figure of Solomon might be taken as the exemplar of the wise ruler, as he was in Bacon's writings (catalogue no. 53), and could be identified with a contemporary learned monarch, such as James I. Such typology could have controversial implications, for example in the rival characterizations of the Church of England as an ark of salvation and as the false idol, Dagon. Relatively few early modern readers of the Bible continued the medieval practice of a fourfold interpretation of scripture (literal, allegorical, tropological, and anagogical). They tended instead to favour more mystical, allegorical readings, often based on a complex typology, or more usually to rely on the elucidation of the apparent literal meaning of the text. Despite the philological elements introduced into the literal exegesis of scripture by humanist scholars, both of these early modern patterns of biblical interpretation grew out of the medieval scholastic tradition and owed much to it.

The early modern way of interpreting scripture was pre-critical in so far as it regarded the Bible as a special book whose message, although delivered in a particular historical context, transcended time. But it was not pre-critical in the sense of lacking method. In England, at least, individuals were encouraged to read the Bible in an attentive and ordered fashion, so as to preserve the narrative integrity of scripture and to be able to apply for themselves those parts of the Bible which spoke to humanity in general or which referred to specific times in the future. Preachers were taught to have regard for the context of the passages that they expounded. They were supposed to be sensitive to issues such as the time and place in which particular phrases had been uttered or words written. They were aware that certain parts of the Bible required special exegetical care, and that, in places, it might be necessary to desert the literal sense in order to bring out more important moral truths or defend the inspired word of scripture from the charge of absurdity. However, they also knew that such departures from normal critical practice should be sanctioned by reason, and, if possible, by the tradition of the early Christian Church.

| |

|

|

catalogue no. 69

|

The emphasis which the early Protestant reformers laid upon a personal encounter with the authentic words of scripture, combined with the value which humanist critics derived from a comparative and philological study of the text, encouraged many to acquire linguistic skills in Greek and Hebrew. These gave learned readers an immediate appreciation of the style of the Bible, albeit one which was sometimes stunted by the poverty of contemporary teaching, especially in oriental languages. Early modern critics were thus not unaware of changes in compositional techniques between different passages and books of the Bible, which were also brought out by the literal translations used by ordinary readers. However, they chose to interpret such material as conveying theological nuances or showing the accommodation of the divine message to particular historical contexts, rather than as a demonstration that the Bible had been composed by a number of different hands over time. On the contrary, the unity of the moral and theological message of the Bible helped to prove that it was the work of a single guiding principle, that of the Holy Ghost.

It was normally accepted among Protestants in the early modern period that the original text of the Bible had been preserved from change and harm by the action of providence. Despite this, new manuscript discoveries and the scrutiny generated by attempts to produce accurate, literal translations helped to channel the activities of many intellectuals into the field of textual scholarship. A number of different theories were developed about the history of the transmission of the text and about alterations which might have occurred to it over time (see catalogue nos.73 to 78). In general, those who argued that the text had changed in some way also believed that it would be possible for Christian scholars to reconstruct the original, as it had been dictated by the Holy Ghost. There was a willingness to accept some human intervention in the editing and transmission of the Bible, but a general belief that this had been intended to preserve not to alter the original. If changes had occurred they were a product of the imperfect historical and linguistic knowledge of earlier editors which could increasingly be corrected as more information became available and skills improved. Such beliefs were consistent with contemporary doctrines of providence as well as with the history of linguistic and political change which had been derived from the Bible itself. They allowed space for textual and critical scholarship without threatening the central position of scripture within reformed religion.

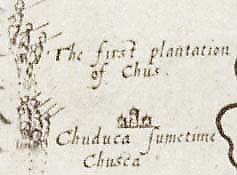

Many critics ranged widely in order to understand the details of biblical history and to establish the exact contexts for customs and practices described in the Bible. Their work increasingly took in comparative materials, drawn from the study of past and contemporary Jewish and eastern religion, as well as applying the findings of textual and material scholarship. Astronomical data was applied to help verify the details of biblical chronology and to establish its true relationship to the secular chronologies of the ancient world. Anthropological and archaeological findings were deployed to try to generate an understanding of obscure practices described in the Bible, such as the true form of the worship of the Jewish Temple. Specifics which were derived from the results of such criticism might find their way in turn into the interpretation of prophetic texts, the understanding of whose mystical language depended on a detailed knowledge of the order of past events and the forms of biblical religion. The growing reliance of early modern critics on historical and natural evidences did not usually compromise their acceptance of the literal sense of scripture. On the contrary, the testimony of the natural world in the past, the present, and the future seemed to many to confirm truths about religion and providence which could be found expressed most clearly in the Bible.

|

|

|

catalogue no. 69

|

However, such reliance on the literal sense of the Bible was not without its problems. In unskilled or untutored hands, the injunction to search the scriptures for oneself could lead to theological errors and to a worrying tendency to justify actions by reference to supposed biblical proofs, found in passages which were quoted out of their true contexts. It was also tempting to resort to allegory or to mystical readings of the Bible when the literal sense appeared obscure or unbelievable, rather than to puzzle over historical contexts or linguistic conundrums. After the Restoration, many orthodox divines, especially within the Church of England, stressed the difficulty of understanding the Bible and the need for assistance from a trained interpreter, such as a priest, when tackling certain kinds of reading. They did so in order to limit the spread of what seemed to them idiosyncratic and often dangerous or heretical interpretations of the Bible. But, in the process, they helped to create a more divided approach to understanding the text. The reformed principles of the perspicacity and sufficiency of scripture thus became more controversial.

A growing awareness of problems associated with the text, and of the divergence between Jewish and Christian exegesis, helped to inspire more heterodox interpretations of the Bible from the time of the Reformation onwards (see catalogue no. 84). Some of these cast doubt on the authorship of scripture; others questioned its historicity. However, such interpretations tended to provoke controversy rather than inspire assent for most of the early modern period. The apparently overwhelming evidence of contemporary scholarship in history, comparative mythology, and natural philosophy seemed to Protestants to support their literal readings of the Bible and the belief that past and present were subject to providential guidance. To place too much stress on minor inconsistencies and doubts appeared in contrast to be evidence of a scepticism which bordered on atheism or of an acceptance of Catholic arguments in favour of the superiority of the teachings of tradition over the findings of reason and individual experience. For most Protestants, the theological as well as the scholarly motivation for continuing to value the literal sense of scripture was thus compelling.

David C. Steinmetz, 'The Superiority of Pre-Critical Exegesis', reprinted in Stephen E. Fowl (ed.), The Theological Interpretation of Scripture (Oxford, 1997), pp.26-38; Richard A. Muller, 'Biblical Interpretation in the Era of the Reformation: The View from the Middle Ages', in Richard A. Muller and John L. Thompson (eds.), Biblical Interpretation in the Era of the Reformation (Grand Rapids, 1996), pp.3-22; Patrick Collinson, 'The Coherence of the Text: How it Hangeth Together: The Bible in Reformation England', in W.P.Stephens (ed.), The Bible, the Reformation and the Church (Sheffield, 1995), pp.84-108.

|