Science at Sea

In the age of the sailing ship, successful navigation relied on knowledge and mastery of the winds. Whether becalmed or driven by contrary winds, voyages were subject to delay, while storms could spell disaster.

To cope with the uncertainties of their trade, mariners developed their own wind and weather lore in familiar waters. But as European exploration expanded in the 15th and 16th centuries, sailors faced the uncharted regions of the southern Atlantic, Indian and Pacific oceans.

The sea soon became an object and area of wider study. The astronomer Edmond Halley, famed now for the comet named after him, went to sea in the late 17th century. He investigated the trade winds so vital for commerce as well as the variation of the magnetic compass.

Weather at sea was recorded in ships’ logs and the oceans long remained significant for meteorology: the first truly international conference on meteorology met in 1853 specifically to discuss improvements to maritime meteorology.

Observatories

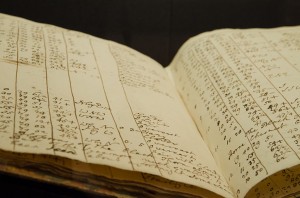

A record of systematic meteorological information recorded at Radcliffe Observatory in Oxford by Thomas Hornsby, appointed Oxford’s Savilian Professor of Astronomy in 1763.

Astronomers have always been acutely aware of the weather: clouds can ruin a night’s observations. More subtly, atmospheric refraction – the deviation of light from a straight line as it passes through the atmosphere – affects astronomical measurements. Observatories became key sites for the development of meteorology not least because refraction was found to depend on temperature, pressure and humidity.

The culture of astronomy was also a perfect fit for meteorology. Astronomers were trained in the discipline of observation: they were accustomed to the careful recording of measurements, to the requirements of instrumental calibration, and to the practical issues of managing paperwork from observing programmes that might run for decades.

Permanent national observatories, established from the 17th century onwards, became major centres for meteorology. By the 19th century, even amateur astronomers were recording the weather in printed forms distributed nationally and internationally.

Hartwell House in Buckinghamshire, with the dome of the small observatory in the centre of picture.

Into the Air

Meteorology is the science of the atmosphere. Yet most observations until the 19th century were conducted on the ground, leaving a vast swathe of phenomena beyond direct investigation.

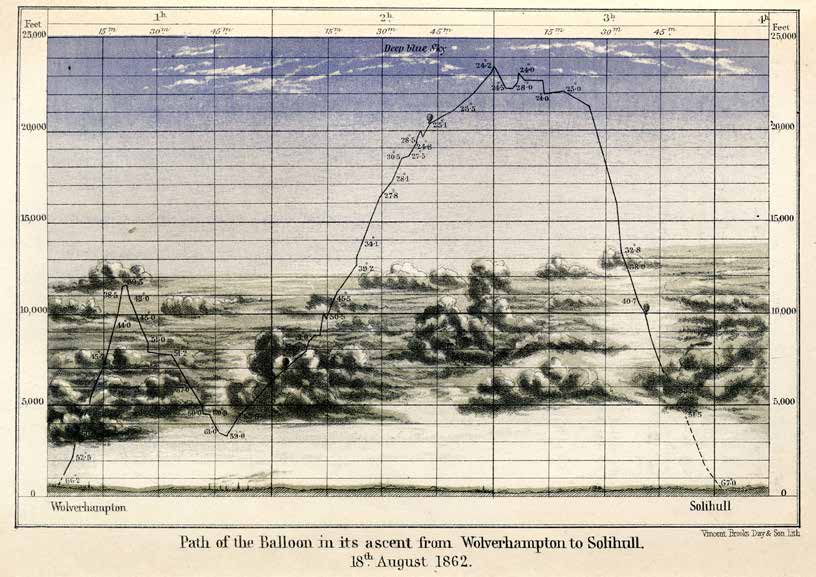

The earliest attempts to overcome this limitation were by climbing. The Alpine journeys of Horace-Bénédict de Saussure in the late 18th century were particularly significant in extending the reach of meteorology. The development of the hot air balloon provided a dramatic and romantic alternative, as intrepid meteorologists risked their lives to reach higher into the atmosphere.

A less perilous approach was to use light, compact self-recording instruments attached to unmanned kites and balloons. Balloons are still used today, bearing ‘radiosondes’ that transmit data back to a radio receiving station on the ground below.

The record of an 1862 meteorological balloon flight from James Glaisher’s Travels in the Air (1871).

Weather by Radio

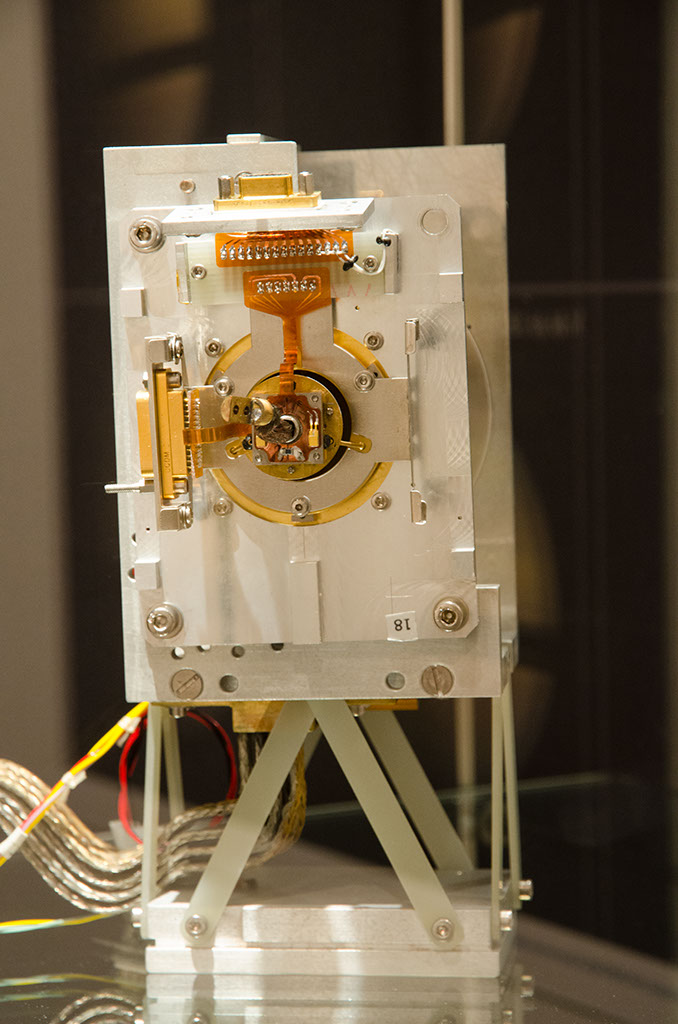

Radiosondes are meteorological instruments with an onboard radio transmitter to send their measurements back to a receiving station on the grgound. The first successful radiosonde in the UK was the ‘Kew’ Met Office sonde, in use from 1939. An improved Mark 2 was used from 1945 until the 1960s.

Pictured right is a Mark 2. The standard configuration carried sensors for pressure, humidity and temperature which projected beyond the body of the sonde. Only the temperature sensor survives here, minus its housing. Despite appearances, the three linked cups are not an anemometer but a windmill. The spinning of the windmill turns a mechanical switch which selects each of the sensors in turn, since only one sensor signal could be transmitted at a time.

MHS Objects in the Exhibition

- 75711 Balloon-Borne Radiosonde Meteorological Instrument, by VIZ Manufacturing Company,

Philadelphia, c. 1976 - 89766 Mark IIb Radiosonde, by Whiteley Electrical Radio Co Ltd, English, 1960s.

- 57389 Dines’ Balloon Meteorograph, British, Early 20th Century.

Out of this World

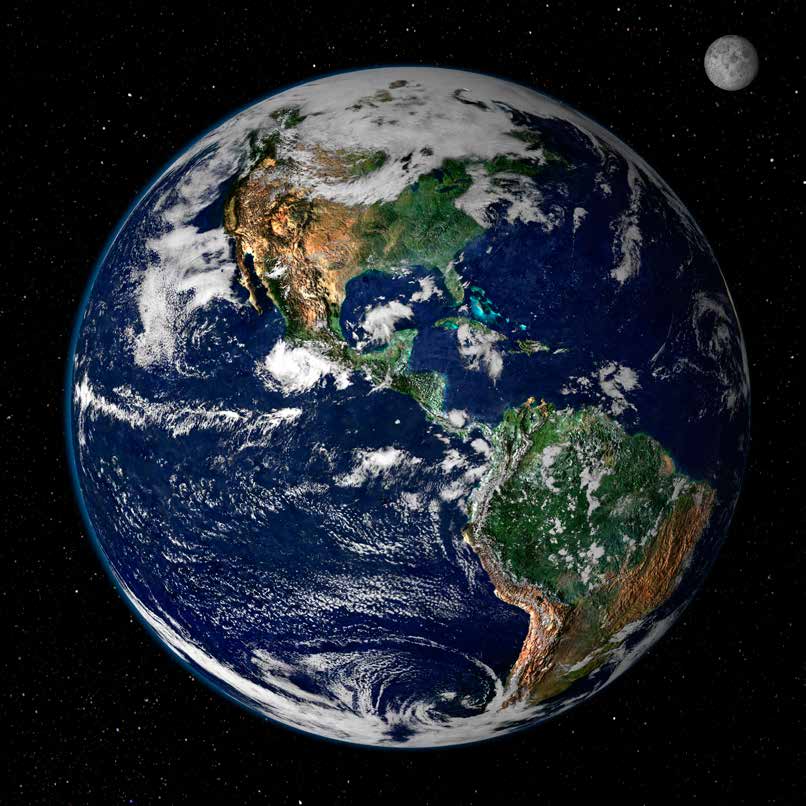

The first successful weather satellite was launched in 1960. Many countries now operate their own meteorological satellites, collecting a wide range of data and directly contributing to improvements in forecasting ability over recent decades.

But meteorology is no longer solely focused on the Earth. The science now considers atmospheres in the plural, based on missions to other planets and moons in the solar system. Many spacecraft have been sent to Venus and investigations of the large ‘gas giants’ of Jupiter and Saturn are continuing. National agencies typically co-ordinate the complex process of designing, procuring and testing satellites and space probes. Large corporations often deliver the rockets which lift spacecraft into orbit. But universities have had a significant role in creating the instrumentation which delivers the science programmes of space research.

35,000km up – a composite image created from land surface data returned by NASA’s Terra satellite and a snapshot of the Earth’s clouds from NOAA’s GOES satellite.