Celia Joicey

Our eyes are only glass windows; we see with our imagination

William Gilpin (1792)

For the past year, the University of Oxford has been playing host to a series of experiments in the visual arts. Five artists have been asked to explore the subject of science and to make meaningful connections with their own work.

One of these experiments has involved a collaboration between the artist Susan Derges and the Museum of the History of Science. The project began when the Museum was approached by the Ruskin School of Drawing and Fine Art to see whether it would house a residency during Year of the Artist. The other University-based schemes have concentrated on making links between artists and practising scientists, but it was felt that the history of science could provide an alternative and equally stimulating source of enquiry.

Susan Derges's proposal - to explore the Museum's 'cabinets of curiosity' using the four elements of earth, water, air and fire as a guide - immediately presented the organisation with new ways of thinking about its collections. From the Museum's staff, Jim Bennett, Stephen Johnston and Giles Hudson responded by selecting a series of historic texts for the artist to consider. Natural Magic, the title of the residency, is a reference to one of these texts, a famous study of popular natural and physical science by Giambattista della Porta, first published in 1558.

A Renaissance scholar, della Porta is renowned for the broad spread of his scientific interests - encompassing everything from cosmology, geology and optics to poisons and cookery - and for his beguiling observations. Della Porta's writings helped Derges to make the necessary leap of imagination from the Museum's holdings to the spell-binding experiments in which the exhibits were originally used. Furthermore, Natural Magic includes the first description of a camera obscura, and the passage entitled 'How by night an image may seem to hang in a chamber' informed Derges's approach to photographing her subjects.

The artist decided to use her residency to recover the sense of imagination and wonder in science. At the outset of the project the building was undergoing refurbishment. When excavations on the foundations unearthed old chemical vessels, alongside human and animal remains, the artist started thinking about the relationship of these objects to early scientific practice. The archaeological finds were surprisingly intact and from their interpretation the final exhibition was shaped.

'The material found in the basement,' says Derges, 'had once formed part of an ancient scientific laboratory. The objects provided a potent reminder of an era of science when there was less separation of disciplines, when anatomy would have been practised alongside chemistry or celestial observation, and when imagination and subjectivity were inseparable from scientific enquiry. The basement, which I knew was to become the Museum's temporary exhibition space, offered a strong contrast to the light and airy galleries above where instruments of mathematical science, such as astrolabes and sun dials, are housed. I wanted to use my work to evoke the magic of natural philosophy and the allure of experiment.'

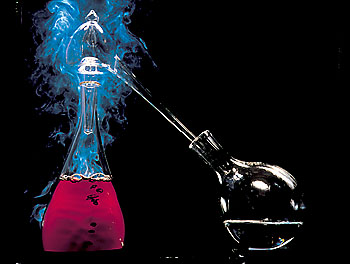

Together, the manuscripts and apparatus inspired the artist to recreate the spirit of early Renaissance experiments. 'In his text,' Derges explains, 'della Porta describes the process of distillation in lyrical and imaginative language comparing the process to the showers and dew of heaven - "as the daughter, the mother". I was interested in distillation because it suggested an activity that could be used to relate some of the finds and the phenomena associated with them to internal processes of change - a concern of alchemy, which it is believed was practised on the site of the Museum. I liked the idea of the observer's imagination projected onto and into the processes within the retorts and alembics so that the experiment became a means of personal transformation as well as scientific observation.'

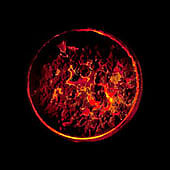

Derges began by commissioning a glassblower to produce close copies of the traditional distillation vessels. The process of distillation uses heat to turn a substance to vapour, and then uses cold to condense and collect the resulting liquid. The apparatus comprises a flask with an alembic head and a side neck inserted into a separate vessel where the distillate can collect. 'The making of alcohol from wine,' says the artist, 'or the distillation of aqua vitae was part of alchemical practice. I wanted to make images of this process that reflected the spiritual dimension of the work in a way similar to the use of grape and wine motifs as resurrection symbols in Flemish still lifes. The whole process of pulping, fermenting, boiling and condensing became a sequence of images that symbolise a process of internal as well as exterior change and informed the four large images of the elements.'

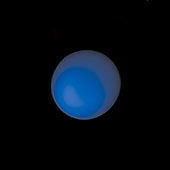

By observing and capturing the conversion of grapes into alcohol, Derges became aware that her images could be abstracted as metaphors for the magical aspects of scientific discovery, and her work brings all these readings together. Four large Ilfochromes representing the four elements are set alongside smaller back-lit light boxes which narrate the creation of aqua vitae. Four display cabinets set along the opposite wall bring together unlikely juxtapositions of Museum objects, selected by Derges and the Museum staff, all of which relate to one of the elements involved in the distillation process. In addition, passages and illustrations from various historical manuscripts, particularly Robert Fludd's Utriusque Cosmi, shed further light on the numinous quality of scientific exploration.

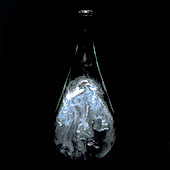

Another sequence of images in the exhibition focuses on the theme of metamorphosis and echoes the chemical narrative of the distillation process. In the past, Derges has recorded the life cycle of the frog and this new work reprises her investigations in this area by returning to an observation of frogspawn and toadspawn. The spawn patterns inside a round-bottomed flask have an abstract quality and generate associations with the sorts of images seen down a microscope or through a telescope. As such, they provide a means of thinking about scale, the relationship between science and nature, and the processes of recognition

and transformation.

The Oxford residency is not the first time that Susan Derges has animated past scientific research. On a previous occasion, she used experiments to explore the role of the viewer in the experience of science. In her photographic series of 1991 called The Observer and the Observed, Derges updated an experiment first performed in 1889. Using a strobe light, the artist broke up a jet of water to produce a standing wave form which, in the photographs, appears as a series of droplets suspended in space. Behind the droplets is a seemingly indistinct image of the artist's face which, when viewed from a distance, achieves blurry focus. Close up, the viewer sees the inverted image with much greater clarity, refracted as it is through the lens of each watery bead.

Derges's photographs are not just intended to illustrate what the early scientists saw. They conjure up what they felt and imagined, too. This approach is as much a comment on the making of art as it is on the pursuit of science. In the late 18th century, Wordsworth famously defined the making of art as 'emotion recollected in tranquility... the emotion is contemplated till by a species of reaction the tranquility gradually disappears and an emotion, kindred to that which was before the subject of contemplation, is gradually produced and does itself exist in the mind'. The parallels with Derges's response to the writings of della Porta are clear, and the strings of toadspawn glowing in a glass flask or the shroud-like smoke coiling sensuously in a bell jar arouse a similarly personal reaction.

The artist's attempt to deal with the emotional and visual content of the history of science mirrors the reflections of past scientists. Sir Humphry Davy, President of the Royal Society, tutor to Michael Faraday and a leading chemist of the early 19th century readily acknowledged the importance of emotion in his work. 'Whilst chemical pursuits exalt the understanding,' he once wrote, 'they do not depress the imagination or weaken genuine feeling.' Too often, science is depicted as a detached and objective undertaking. Art, by contrast, is acknowledged to be about feelings, connections and instinct. By using the four elements as an organising principle, Susan Derges helps us to see the objects and history of science through imaginative eyes and reveals unexpected affinities between scientific and artistic ways of making sense of the world.

Celia Joicey is Publishing Manager at the National Portrait Gallery in London