Aquatint, Hand-Coloured, of the Interior of the Radcliffe Astronomical Observatory, Oxford, by J.Bluck after E. Mackenzie, for Rudolph Ackermann, 1814. Inv 19446 [1]

Our prints collection contains a number of items relating to Oxford and to the history of Oxford museums and institutions, including the Radcliffe Observatory.

This aquatint [2] shows the observer’s room of the Radcliffe Observatory, built in 1773 and in use until 1934, by James Wyatt and modelled on the Tower of the Winds in Athens. The first Radcliffe Observer, Thomas Hornsby, commissioned astronomical instruments from some of the eighteenth century’s finest makers including John Bird, Dollond, and Shelton. In the 1930s the Trustees of the Radcliffe Observatory donated the majority of the original equipment to the museum. The near-complete collection of an eighteenth century observatory and equipment used for scientifically important observations is of great value to Oxford and the wider world. Many of the objects seen in this aquatint are held in the museums collections and can be seen on display.

Steel Engraving, The Ashmolean Museum, by J.Le Keux after F. Mackenzie, Published by J.H. Parker, Oxford, C.Tilt, London, J.Le Keux, London, 1834. Inv 14228 [3]

Engraving, The University Museum, Drawn and engraved by J.H. Le Keux, Published by J.H. Parker, Oxford, 1859. Inv 13898 [4]

Le Keux

There are many examples of portrayals of Oxford views in the collection, particularly engravings by members of the prominent Le Keux engraving family.

John Le Keux (1783-1846) was the first notable engraver with brother Henry Le Keux (1787-1868) and son John Henry Le Keux (1812-1896) contributing further significant work. It was not uncommon for many members of the same family to become engravers and other engraving families whose work is present in our collection include the Heath family [5]; notably James and son Charles.

The Le Keux plates in our collection are mostly attributed to John Le Keux whose characteristic style was epitomised by fine yet free lines and was predominantly focused on architectural engraving. He produced plates for numerous notable nineteenth century works on architecture.

The plates by John Le Keux after Frederick Mackenzie depicting The Hall of Wadham College [6] and the old Ashmolean Museum building (now the Museum of the History of Science) are associated with James Ingram and Le Keux’s Memorials of Oxford which gave descriptive accounts of the University colleges, halls, churches and public buildings of Oxford. The plates are printed from steel plates rather than the traditional copper, something that became widespread after the 1820s, and enabled significantly more impressions to be made before the plate became worn. Steel was much more difficult to engrave than copper so ‘steel engravings’ are often mostly made up of etched lines.

John Henry Le Keux was similarly talented in engraving. He also focused primarily on architectural engraving and worked with other notable figures such as John Ruskin, engraving Ruskin’s illustrations in The Stones of Venice (1851–3) and Modern Painters (1856–60) as well as exhibiting drawings at the Royal Academy. He also engraved his own designs for the Oxford Almanack (1855-70).

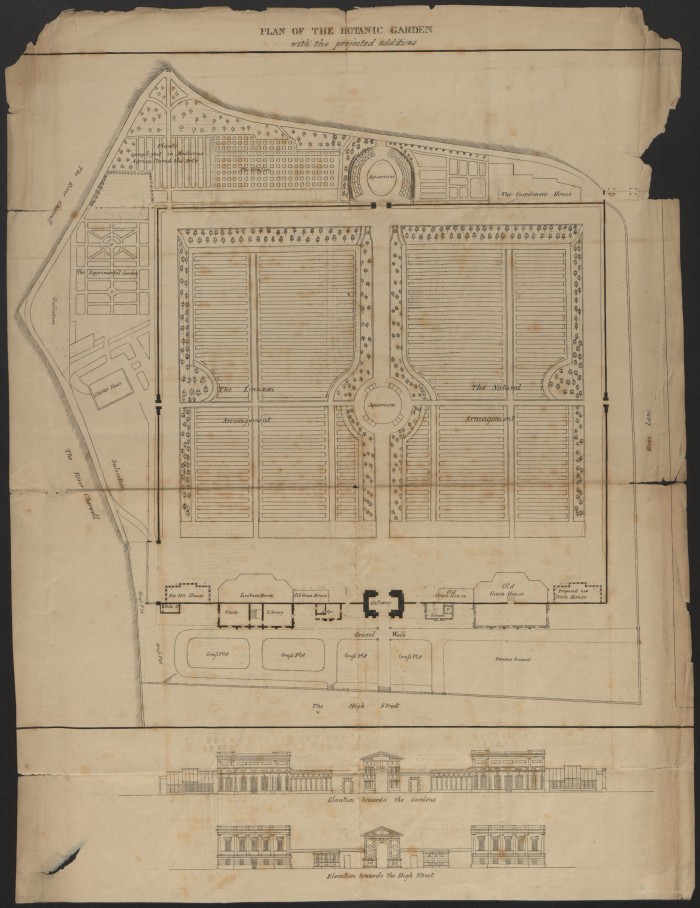

Oxford Botanic Garden

The first plan of the Oxford Botanic Garden [7] was made by David Loggan in 1675 and shows four main enclosures within the garden walls, each containing four series of geometrically arranged beds. The layout shown in our nineteenth century plan shows the same fundamental design.

Engraving, Plan of the Botanic Gardens, with the projected additions. Oxford. 19th Century. Inv 14105 [8]

The garden was founded as a physic garden in 1621 following funding from Henry Danvers, 1st Earl of Danby. It is one of the oldest botanic gardens in the world, and was the first to be established in England. A site close to the River Cherwell on land belonging to Magdalen College was chosen, and the site was raised to prevent flooding.

The early physic gardens had an academic purpose in the study of medicinal plants; the mission of the Oxford Botanic Garden was ‘the glorification of the works of God and for the furtherance of learning’. The age of exploration brought a new purpose to botanic gardens in cultivating new species brought back from far-flung expeditions.

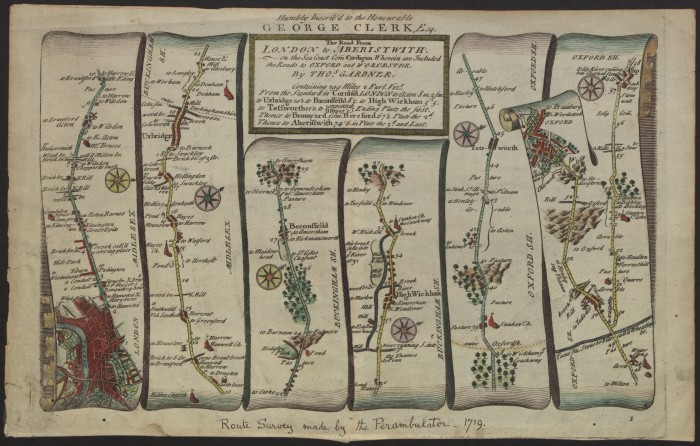

London-Oxford Map

The Road from London to Aberystwyth, by Thomas Gardner is one of the 100 road strip maps from the first small-scale re-engraving from John Ogilby’s Britannia (first published 1675) and Mr Ogibly’s Tables of his Measur’d Roads (1676), published in 1719 as The Pocket Guide for the English Traveller. This section plots the journey route from London to Oxford.

Gardner’s edition of the road maps provided a more useful and practical version. The preface to The Pocket Guide states that Ogilby’s maps were more useful as ‘Entertainment for a Traveller within Doors, than a Guide to him upon the Road’. This suggests that the Ogilby version would rarely have been used by travellers on the road.

Gardner’s pocket guide was published the same year as John Senex’s Actual Survey of all the Principal Roads of England and Wales who in turn claimed that his maps were ‘improved, very much corrected, and made portable’. The emergence of map collections such as Ogilby’s were part of an emerging cartographic literacy in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

Engraving, Hand-Coloured, The Road from London to Aberystwyth, by Thomas Gardner, London, 1719. Inv 14431 [9]