“It looks like a miracle.” (Howard Florey, 1940)

“Every hospital had a ‘septic’ ward, filled with patients with chronic discharging abscesses, sinuses, septic joints, and sometimes meningitis … chambers of horrors, seems the best way to describe those old septic wards.”

Dr Charles Fletcher, who gave the first penicillin injection at the Radcliffe Infirmary in 1941, on life before penicillin

Making Miracles?

Fleming had first discovered that the ‘juice’ from a mould could destroy bacteria in 1928. But he was unable to purify, stabilise and concentrate this juice, which he named penicillin. Ten years later Florey’s collaborator Ernst Chain picked up on Fleming’s almost forgotten work and decided to pursue its potential.

Another member of the Oxford team, Norman Heatley, developed ingenious apparatus to grow the mould and extract, purify and concentrate small amounts of penicillin. By 1941 the team was ready to conduct the first human trials. After saving patients with otherwise fatal infections at Oxford’s Radcliffe Infirmary it was clear that penicillin was an almost miraculous antibiotic.

The challenge was to manufacture large quantities. Wartime Britain lacked the resources so Florey and Heatley secretly travelled to America in 1941 to seek the help of Britain’s allies. The Americans provided not only resources, but also new science and technologies that enabled the production of penicillin on an industrial scale.

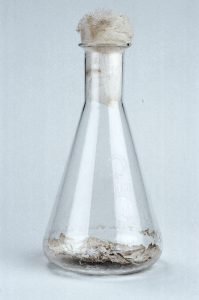

The first penicillin extracted in Oxford came from a mould culture grown in flasks. Around 150 flasks of culture were required to produce a small sample of penicillin. The strength of penicillin preparations was measured by placing samples in cylinders in a culture dish and recording the size of the ring of bacteria killed off. The Oxford group defined a standard unit of potency and distributed samples to calibrate research elsewhere.

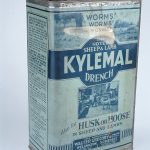

Norman Heatley began work on penicillin in 1939. He was a meticulous record keeper, maintaining detailed diaries and laboratory notebooks. On the same page, he recorded momentous days in history and in his own career. Tracking the experiments he listed in detail the various vessels used to grow penicillin. Heatley’s vessels are displayed below.Norman Heatley’s early efforts to grow penicillin used any convenient vessels that could provide a large surface area for the mould’s culture medium. The laboratory became home to cans of sheep dip, pie dishes, bed pans and biscuit tins. Seeking to increase production Heatley designed a rectangular ceramic vessel that could be stacked. In total, 700 vessels were made by the Staffordshire Potteries firm James Macintyre and Co. Ltd. The first batch was seeded with spores of the mould on Christmas Day 1940 and the resulting penicillin was used to treat the first six patients in the Radcliffe Infirmary in Oxford in 1941.

When early tests on mice proved effective the Oxford team transformed their laboratory into a penicillin production centre for the first human trials. Special apparatus was devised for the different steps: the pistol removed penicillin-infused fluid from the culture vessels. Norman Heatley designed a semi-automatic apparatus to then continuously extract and purify the penicillin; the original control panel survives. Several more steps such as separating with a funnel were required to create powdered penicillin.

From a Room to a Bottle

The film shows some of the key steps used in the laboratory production of penicillin. Surviving apparatus and historic photographs (shown in the exhibition) are animated to reveal the complex processes needed to extract and purify the substance.

Credit: Computer animation developed by Carl Schwedes, Hochschule für Technik und Wirtschaft, Dresden

[ Next: Consumption ]