There were literally hundreds of observers of the transits in 1761 and 1769. Their observation reports flooded into learned periodicals like the Royal Society's

Philosophical Transactions, but also appeared in popular magazines.

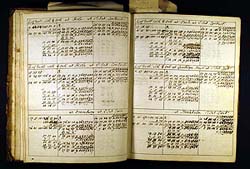

.After the events themselves came the hard labour of calculating the results. This meant not just routine number-crunching, but the more subtle sifting and assessment of observations. Should all reports be given equal weight? Each analyst or “computer” generally selected only a few reports considered especially trustworthy.

.The problems of calculation combined with those of the observations themselves. Even the best-equipped observers had often encountered unexpected difficulties. Some astronomers were simply unlucky and were prevented from observing by cloudy skies.

.Rather than converging towards a single value for the distance from the Earth to the Sun, different astronomers arrived at slightly different results. This spread of values left the sense that “the most noble problem in nature” was yet to be conclusively settled.

The Transit Method

The Transit Method Transits in Print

Transits in Print Staging the Transit

Staging the Transit A Commercial and

A Commercial and  Transit Geography

Transit Geography Timing the Transits

Timing the Transits Viewing the Transits

Viewing the Transits Transit Places

Transit Places Oxford Observations

Oxford Observations Results

Results