Harry in his Royal Engineers officers uniform complete with signallers armbands, c.1914.

Image courtesy of the Royal Society.

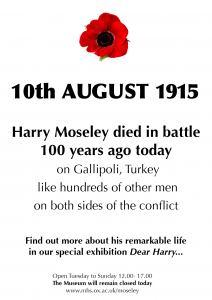

Today, 10 August 2015, marks the centenary of the death of Second Lieutenant Henry Gwyn Jeffreys Moseley (known to friends and family as Harry), killed in action at Gallipoli, Turkey aged just 27. Harry had enlisted for officer training in the Royal Engineers in mid-October 1914 and trained as a signals officer at Aldershot and Salisbury camp. In February 1915, Harry’s unit was attached to the 13th Division of Kitchener’s ‘New Army’ and Harry was allocated responsibility for the communications of the 38th Brigade.

Harry and his unit assumed that they would be sent to France and the Western Front but instead Gallipoli, Turkey was there destination where they were sent along with a total of over half a million other Allied soldiers to fight soldiers from the Ottoman Empire, later Turkey.

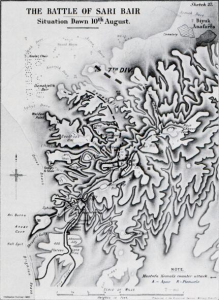

“The battle of Sari Bair. The situation at dawn, 10 August 1915.” from Aspinall-Oglander, Brigadier General C.F. Official History of the Great War. Military Operations. Gallipoli Volume 2: May 1915 to the Evacuation. With the companion volume of Appendices. (1932).

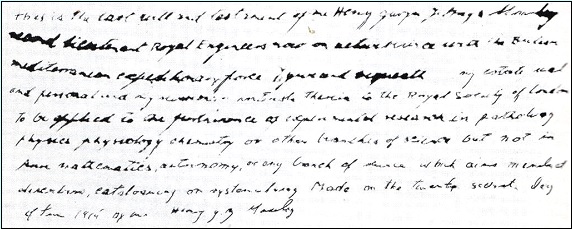

In June 1915, Harry and his division arrived in Alexandria where Harry wrote his will leaving everything to the Royal Society to support original scientific research. By July, these inexperienced soldiers of Kitchener’s ‘New Army’ had arrived at Helles, at the southernmost tip of the Gallipoli peninsula. There they gained essential combat experience against Turkish troops before being sent to Murdos harbour on the island of Lemnos, a staging area for the upcoming fresh invasion further north near ANZAC cove.

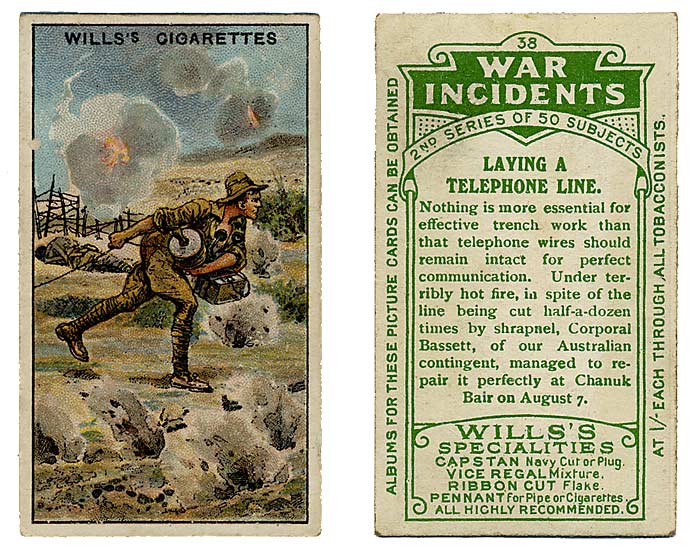

Having landed up the coast at ANZAC cove in early August, the objective of the British troops and their allies was to take a precarious salient on Chunuk Bair (Turkish: Conk Bayırı) in what became known as the Battle of Sari Bair. In the murderous four days that followed thousands of men on both sides died.

After the landing, the 13th Signals Company of which Harry was a member was put to work to support this attack. Cables were laid to 40th Brigade at Damakjelik Bair as well as the Indian and Australian Brigades taking part in the attack. On 7 August, the 38th Division led by their brigadier C.H. Baldwin led a desperate attack against the northern portion of Chunuk Bair. The Division did not reach its objective but instead became stuck in an area known as “Farm Hill” about 300 yard west of their initial objective. Despite leading an attack later that day (7 August), the division remained at Farm Hill and held it for 8-9 August but never reached the high ground at Chanuk Bair.

Early on the morning of 10 August, a Turkish counter-attack took place: machine guns fired down on the position of the 38th Division including Moseley while 30,000 Turks poured down over the summit of Chanuk Bair attacking “Farm Hill”. Combat was hand-to-hand and was later described in a British record of the battle thus:

So desperate a battle cannot be described. The Turks came on again and again, fighting magnificently, calling upon the name of God. Our men [the 38th Division] stood to it, and maintained, by many a deed of daring, the old traditions of their race. There was no flinching. They died in their ranks where they stood.

Cigarette card of Gallipoli signals work at battle of Chunuk Bair.

Image available in the public domain via Department of Veterans’ Affairs, Commonwealth of Australia.

One of these soldiers killed was Harry Moseley. His body, like that of so many others, was never found, but his name is commemorated on Helles Memorial.

Harry was one of many soldiers killed or injured on both sides during the Gallipoli Campaign (Turkish: Çanakkale Savaşı): over 100,000 men were killed and over 400,000 killed or injured on both sides during the brief campaign which ran from 25 April 1915 through to early January 1916. In his death, Harry was both ordinary and extraordinary. He was an ordinary representative of 100,000 men killed on both sides as well as the hundreds of Allied soldiers killed near Chunuk Bair on 10 August 1915 but in the way that death was reported and later commemorated he was both extraordinary and exceptional.

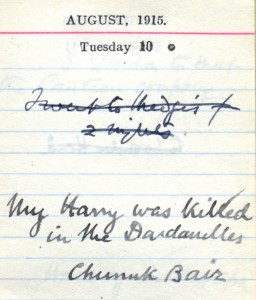

News of Harry’s death reached his family on 30 August when the War Office telegram arrived to the home of his mother Amabel at 2.15pm or thereabouts according to her diary. She immediately sent for Margery, her daughter and Harry’s sister. Amabel went back in her diary to 10 August – the day her son died – and wrote in somewhat shaky handwriting, “My Harry was killed in the Dardanelles Chunuk Bair”.

Amabel wrote to the War Office in early September enquiring as to further news of her son’s death, noting that “any information that you can give will be gratifying to me”. The War Office was unable to provide any further details and it is believe that the report of Harry’s death being a shot to the head by a Turkish sniper while telephoning through an order as later reported in Rutherford’s Nature obituary was communicated informally by a soldier from Harry’s division who had survived the attack.

A mere two days after the news of Harry’s death had reached his family, Harry’s death was reported in “Fallen Officers – List of Casualties” the Times on 1 September under the sub-headline “A Brilliant Physicist”. News of Harry’s death spread quickly. Newspapers in Britain reported it under headings such as “Sacrifice of a Genius” and “Too Valuable to Die”. Even German newspapers commented on his loss, though he was now formally an enemy.

Across the political and military divide, the international scientific community was shocked by Harry’s death. His former supervisor Sir Ernest Rutherford especially condemned the waste. Upon receiving the news of Harry’s death, Rutherford wrote a heart-felt letter and obituary in Nature published in September 1915, a month after Moseley’s death:

Scientific men of this country have viewed with mingled feelings of pride and apprehension the enlistment in the new armies of our promising young men of science – with pride for their ready and ungrudging response to their country’s call, and with apprehension of irreparable losses to science.

Rutherford concluded his heartfelt obituary of Moseley with a plea that Moseley’s death not be in vain:

It is a national tragedy that our military organisation at the start of the war was so inelastic as to be unable, with a few exceptions, to utilise the scientific services of our men, except as combatants in the firing line. Our regret for the untimely death of Moseley is all the more poignant.

Rutherford along with Harry’s mother Amabel began to assemble recollections and results of Harry’s work and to gather together his scientific legacy. However, Harry’s untimely death meant he was not eligible for the 1916 Nobel Prize for Physics which many thought his achievements deserved. Rutherford, who had tried unsuccessfully to get Harry out of frontline service, argued strongly that scientists should put their talents to use in research aimed at meeting military goals in wartime rather than being sent to fight and die on the battlefield. By the end of the war, Rutherford’s goal had been achieved in part due to the immense impact of Moseley’s death.

Nearly sixty years after Moseley’s death, Isaac Asimov wrote,

In view of what he [Moseley] might still have accomplished … his death might well have been the most costly single death of the War to mankind generally.

Memories, recollections, and commemorations of Harry, his life and scientific legacy, continue through to the present day: there was a moving evensong service on Sunday 9 August 2015 at St Giles’ church in Oxford of which Harry was a parishioner and whose name is the second of seventeen names marked on their World War One memorial of parishioners killed in the war between 1914 and 1919. His named is also featured on war memorials at Summer Fields school in North Oxford (a school league/house is also named after Moseley), Eton College, and Trinity College, Oxford as well as the Helles Memorial at the southern point of the Gallipoli peninsula in Turkey with the latter being recently visited by our director Dr Silke Ackermann on a visit to Gallipoli in Harry’s footsteps. We too remember Harry with our exhibition Dear Harry…: Henry Moseley, a scientist lost to war at the Museum of the History Science which tells the moving and personal story of the life and legacy of Henry ‘Harry’ Moseley – son, scientist, and soldier – and is timed to mark both the centenary of the Gallipoli Campaign and the centenary of Harry’s tragic death as well as those hundreds of men killed on both sides at Gallipoli on 10 August 1915.

Further information about the Gallipoli Campaign

All About Turkey: Gallipoli campaign

Australian War Memorial: Gallipoli

BBC iWonder Guide: “Gallipoli: Why do Australians celebrate a military disaster?”

Imperial War Museum (IWM), UK: The Gallipoli Campaign by Josh Blair

Imperial War Museum (IWM), UK: What You Need To Know About The Gallipoli Campaign by Nigel Steel

The Long, Long Trail: Gallipoli