The stories of the Garden of Eden, Noah's Ark, the Tower of Babel, and the Temple of Solomon are among the best known in the Old Testament. They were alluded to frequently during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and were often used at that time to frame accounts of the progress of knowledge. The narrative history which could be found in the Bible presented a coherent story of the growth and decline of knowledge, in which moral and spiritual factors helped to determine natural and practical outcomes.

As metaphors of knowledge, the four stories gave information about both the acquisition and the ideal state of human understanding. But they also issued warnings about the necessary difference between human and divine knowledge and suggested ways by which knowledge might be married to piety and wisdom in order to achieve an improvement in the condition of mankind. The image that they conjured up was thus both hopeful and threatening. It demanded that human beings temper material and intellectual change with spiritual or moral development. The stories seemed to many to allow for the possibility of transforming the world through the application of human intellect and endeavour. Yet they also emphasized the contemporary belief that the earth had once been a better place, and that human ignorance and suffering were themselves the products of disobedience, error, and folly. The knowledge which was needed to change human life and the natural environment for the good depended on an understanding of the dangers of moral frailty as well as of the achievements of intellectual ingenuity. That understanding could best be developed through an awareness of biblical history and a sense of the working of providence, both of which were enhanced by acquaintance with the lessons of the Garden, the Ark, the Tower, and the Temple.

| |

|

|

catalogue no. 36

|

The Garden of Eden provided the setting for the Fall, a transformation which brought about the loss of both spiritual and intellectual perfection, corrupting the nature of humans and of the surrounding environment. The Garden symbolized the ideal state, when the earth had been spontaneously fertile, labour was easy and fulfilling, and human activity had been grounded on a complete knowledge of both words and things. A return to this paradise was considered by some in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries to be possible through the restoration of learning, and through striving to bring the earth and its inhabitants back to a pristine state of grace. It could also be achieved by practical measures, such as the establishment of botanical gardens, which reunited the plants of the world in a single space, or the planting of fruit trees, whose cultivation mimicked the dutiful dressing of the Garden of Eden by its first inhabitants, Adam and Eve. By the zealous investigation of nature and the searching out of new varieties of plants and techniques of husbandry, the world might be rescued from corruption and infertility. Hard labour could make the Garden grow again, and restore the knowledge which humans had once employed to govern nature in paradise.

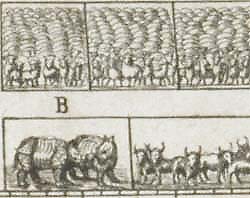

The hopeful message of the Garden was reinforced by the story of the Flood and of Noah's Ark, which told how God had restored humanity's dominion over the earth, and how he had preserved the innocent parts of his creation from the destruction which punished the corrupt. The Ark also seemed to provide a pattern for a number of actions that might help to recreate human power over nature, lost initially at the Fall. It was an inspiration to collect animals and natural objects, and then to classify them as a step towards the recreation of true knowledge. Applied as a metaphor, the Ark allowed contemporary collectors to become Noahs. Their collections came to represent new Arks, in which learning could be expanded and completed. The knowledge which might be amassed in these modern Arks was to be part of an encyclopaedic compendium of nature. Ordered by the application of reformed philosophical principles, it would mirror and rival the comprehensive understanding of the natural world once possessed by Adam or by Noah. The achievement of this end required the establishment of new techniques and practices of learning and teaching as well as the building of new institutions and collections. Inspired by the story of the Ark, many early modern authors and collectors saw themselves as rescuing human knowledge and understanding of the natural world from neglect and depravity.

But the story of the Ark was accompanied in the Bible by a warning, in the shape of the story of the Tower of Babel. Here, human pride had again led to the loss of control over nature, through the confusion of language with which God had frustrated the overweening ambition of the Tower's builders. The knowledge of the just was humble as well as pure; its achievement depended on the ability of people to overcome the limitations of their fallen state, notably the divisions of language and of race which frustrated real communication. The task of overturning the curse of Babel was one to which early modern scholars therefore had to turn themselves.

|

|

|

catalogue no. 43

|

The mechanism used by God to bring about the dispersion of peoples after Babel had been the multiplication of languages. The study of languages, their relationships and their distribution was thus a tool for discovering how the earth had been peopled after the Flood. It stimulated both linguistic and ethnographic knowledge, and also encouraged the investigation of the natural world. Adam's language, the first tongue spoken by mankind, had been perfectly adapted to understanding the natural world and all the species of things which it contained. It was thought to have survived in a corrupted form until the building of Babel. Although the original, ideal speech of humanity was now lost, its essence could be recovered through the construction of a 'philosophical' language. This would restore the direct linkage between words and things, recreating many of the characteristics of Adam's language. Its grammar would reflect natural relationships unambiguously and would open up the possibility of universal communication once again. The groundwork for the construction of new philosophical languages consisted of the analysis of natural history and the establishment of a profound natural philosophy, based on the species and operations which could be discovered by direct study of the natural world. It combined the endeavours of collecting, experimenting, ordering, and naming which fascinated early modern students of nature and which had once been the occupations of both Adam and Noah themselves. The attempt to reverse the curse of Babel became a means to return mankind to a pristine state of grace and knowledge whose defining characteristics were the complete understanding of philosophy and of the natural world and a renewal of unity between nations through shared language and mutual comprehension.

The negative aspects of the image of the Tower were in turn balanced by the positive vision of the Temple, a building which embodied God's purpose for his people, and which testified to the holy achievement of knowledge correctly applied. The architectural accomplishment of the Temple was understood to have been outstanding, while its inspired design embodied the principles of a divine geometry whose recovery would be a brilliant achievement for practical mathematics. The establishment of a convincing historical case for Solomon's use of a particular architectural style would confer on it an irrefutable legitimacy. Biblical accounts of the Temple demonstrated the significance which God had attached to standards of measure and their importance for the proper regulation of society. The ancient Jewish measures were embodied in the dimensions of the sacred objects of the Temple whose management was entrusted to the holy offices of the priests. Christian scholars of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries felt that it was important to trace the descent of standards of measure and to recover their original values. Just as the recreation of some form of universal language might help to restore the knowledge of the world which had once been enjoyed by Adam and Noah, so the adoption of true universal measures might re-establish human dominion over the form and use of nature. The biblical account of the ancient cubit provided a model for the ideal standard of measurement which encouraged critics to believe that an equivalent universal measure might be based on a natural standard that could be used by men everywhere.

The extraordinary success of Solomon's mathematical ventures pointed to his profound natural knowledge and spiritual virtue. The wisdom which Solomon displayed, and which became his proverbial attribute, could only have been achieved through application, study and systematic work since he lived long after the Fall and the loss by humanity of its original, pure understanding of things. Solomon, and the house which he constructed for God, thus became models for the advancement and application of knowledge through organized, collective effort that inspired the creation of new institutions dedicated to natural philosophical learning and experimentation. As metaphors, they summed up contemporary aspirations to understand and control the natural world, and as historical exemplars they testified to the possibility that such hopes might actually be realized.

| |

|

|

catalogue no. 69

|

The ideas of the humanists and reformers of the sixteenth century encouraged early modern readers of the Bible to interpret the Old Testament as literal history, not as allegory. This led early modern writers about natural knowledge to turn to the stories of the Garden and of the Tower to explain the present state of mankind. It allowed them to see the project of overturning the Fall, and recreating the Ark or the Temple, as an essential part of humanity's return to grace and understanding. The stories of the Old Testament were not just convenient metaphors, let alone fictions, they were facts which taught by example how human beings ought and ought not to behave in order to attain knowledge. Although they were commonplaces of early modern learned writing, the Garden, the Ark, the Tower, and the Temple were especially prominent images in the ideas of a loose circle of authors, projectors, and thinkers which formed in England around the émigré German activist, Samuel Hartlib, from the 1630s to the 1660s. A great deal is known about the work of Samuel Hartlib and his associates during this period of great political, religious, and intellectual upheaval, because of the energetic publishing schemes which they pursued, and because of the survival of most of Hartlib's extensive correspondence.

Letters and books by Hartlib and his friends demonstrate the central place which biblical themes had in their thought. Works on agriculture focused on plans to restore the pristine fertility of the earth through improvements in husbandry, and on the application of new techniques to the creation of beautiful gardens in seventeenth-century Oxford and elsewhere. The botanical knowledge collected in such gardens helped to inspire plans for new arks of learning in contemporary ideas about museums and places for scientific endeavour. The restoration of knowledge which could be achieved in these institutions is exemplified by discoveries made with new scientific instruments, such as the telescope or the microscope, which promised to restore the sensory perfection enjoyed by Adam in the Garden of Eden. The work of classifying nature carried out in botanic gardens and museums was extended in contemporary plans, sponsored by members of the Hartlib circle, for a universal language which would overcome the effects of Babel, and embody in their new names the rediscovered essences of things. Books dealing with the Tower emphasize this linguistic project, as well as the historical understanding of the role of Babel in promoting the dispersion of peoples, and the creation of modern nations. The hopes for a restoration of religion and worship, following on from the rediscovery of true knowledge, are displayed in contemporary plans of the Temple of Jerusalem, and in schemes for its rebuilding.

The works represented in this catalogue provide a view of the activities of the Hartlib circle, as part of a broader picture of the role of biblical interpretation in early modern Europe. They show how stories from the Bible provided coherent explanations for the human condition, and how they also seemed to offer plans for escape into a better world. The inspiration provided by the historical examples found in the Bible may seem strange or foreign to some modern readers. Yet it is surely essential to understand such unfamiliar things in order to make sense of past efforts to investigate and control the natural world. Only by doing so can we begin to unpick our own stories of the development of scientific practice, which have often rested on the achievements and discoveries of the seventeenth century.

Cataloguing conventions

In addition to the author, title and standard bibliographical details for each book, collation details, dimensions of the text block, and the Bodleian Library shelfmark of the edition described are also given. Collation descriptions follow Philip Gaskell, A New Introduction to Bibliography (Oxford, 1972). References in the text cited 'Hartlib Papers' are to: Judith Crawford et al. (eds.), The Hartlib Papers: A Complete Text and Image Database of the Papers of Samuel Hartlib (c.1600-1662) Held in Sheffield University Library (2 CD-ROMs, Ann Arbor, Michigan: UMI Research Publications, 1995, ISBN 0835723682).