Comenius’s Janua linguarum was one of the most successful pedagogical works of the seventeenth century. Initially published in 1631, it was soon translated into a number of European languages, and quickly came to the attention of Samuel Hartlib, who began a correspondence with Comenius in 1632, and published several of his works. Hartlib was unable to obtain the profits of John Anchoran’s English-Latin-French edition of 1633 for Comenius, but was more closely involved in the bilingual English-Latin edition of Thomas Horne (1610–54), published in 1636. Horne’s translation was revised by John Robotham and by ‘W. D.’, whom Anthony Wood identified as William Dugard (Athenae Oxonienses, vol. 2, p.106), and went through a total of ten editions by 1659.

Originally intended as a first reader, for teaching Latin and the vernacular, the Janua linguarum evolved into a thesaurus, many parts of which were devoted to practical information about daily life and the natural world. It was structured into one hundred chapters, each on a different theme, originally made up of one thousand sentences which drew on about eight thousand of the most common Latin words. As it expanded, the linguistic content of the Janua linguarum became more complex, but its careful philosophical structure was preserved. This began with the creation of the four elements, and the nature of the earth, plants and animals, and moved on to human anatomy and physiology before discussing rustic and mechanical arts, philosophy, civil society, and, finally, religion and divine providence.

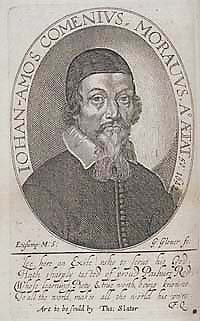

Jan Amos Komenský (1592–1670), known as Comenius, was a bishop of the Czech Unity of Brethren. With his fellow Protestants, he was exiled from Bohemia in 1628, and became a master, and later rector, at the gymnasium of Leszno, in Poland. He developed a Christian philosophy, or pansophia, which sought to harmonize the senses, reason, and scripture. His writings contain strong elements of neoplatonism, as well as a faith in inductive reasoning and empirical knowledge which appealed to English Baconians. Works like the Janua linguarum also betray the influence of his mentor, the encyclopaedist Johann Heinrich Alsted.

Hartlib enticed Comenius to England in the autumn of 1641, at a time when it seemed possible that there might still be a peaceful reformation of church and state. Whilst in London, Comenius worked on his chiliastic Via Lucis (eventually published in 1668), which described, among other things, the work of a Universal College in the perfection of religion and learning and the promotion of the welfare of mankind. The tools with which this College would equip people included ‘new schemes for the better cultivation of all languages, and for rendering a polyglot speech more accessible, and finally for establishing a language absolutely new, absolutely easy, absolutely rational, in brief a Pansophic language, the universal carrier of Light’ (The Way of Light, p.8).

Comenius planned a philosophical language which would be universal, to ease communication and understanding, much as his philosophically-grounded system for teaching in the Janua linguarum had aided the acquisition of tongues. To further Comenius’s work, Hartlib published the heads of his programme of educational reform in A Reformation of Schooles (1642), for whose frontispiece the engraved portrait of Comenius illustrated in figure 37 was cut. However, later in 1642, Comenius was tempted by Louis de Geer to abandon England for Sweden, leaving Hartlib and his friends to work on alone.

Comenius’s work promised to overcome the curse of Babel by re-founding human language on a reformed philosophy, basing it on a simplified range of concepts which reflected a rational analysis of the natural world. The essence of these ideas can be detected in the form of the Janua linguarum, the book which made Comenius’s reputation as a teacher and philosopher.