The Prints Collection includes over 300 printed portraits, most of which are engravings in line or stipple manner. Many of the earlier portraits are taken from frontispiece illustrations to printed books, particularly those from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Most of them were mounted in the nineteenth century and have been separated from the original works. Some were made by printers as standalone portraits.

[1]

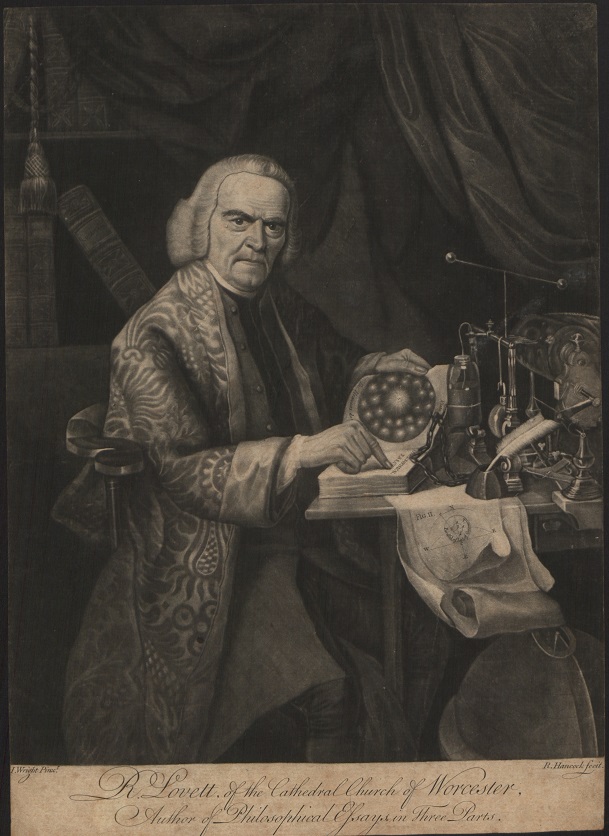

[1]Print (Engraving) of Richard Lovett, after Joseph Wright of Derby, Engraved by R. Hancock, 18th Century, Inv. No. 90133 [2]

For most of the engravings, there is a painted source. The museum holds a painted portrait [3], for instance, of Richard Lovett, writer on electricity, in addition to a mezzotint [2].

Prior to the Renaissance, a coat of arms was used to identify a person. What was considered a good portrait in the Renaissance depicted a socialised self. This could range from exemplary to satirical. A portrait was both a likeness and also a work of art. Portraits can be expected to have a degree of verisimilitude with the subject, but their content was also determined by contemporary artistic trends. Because of the spread of portraiture, the face began to become a more important signifier of identity. The work of the Flemish painter Jan van Eyck was highly influential in the sixteenth century, leading to a broadened range of subjects beyond rulers and nobility. The surrounding details in his portraits indicated the roles and identities of their subjects.

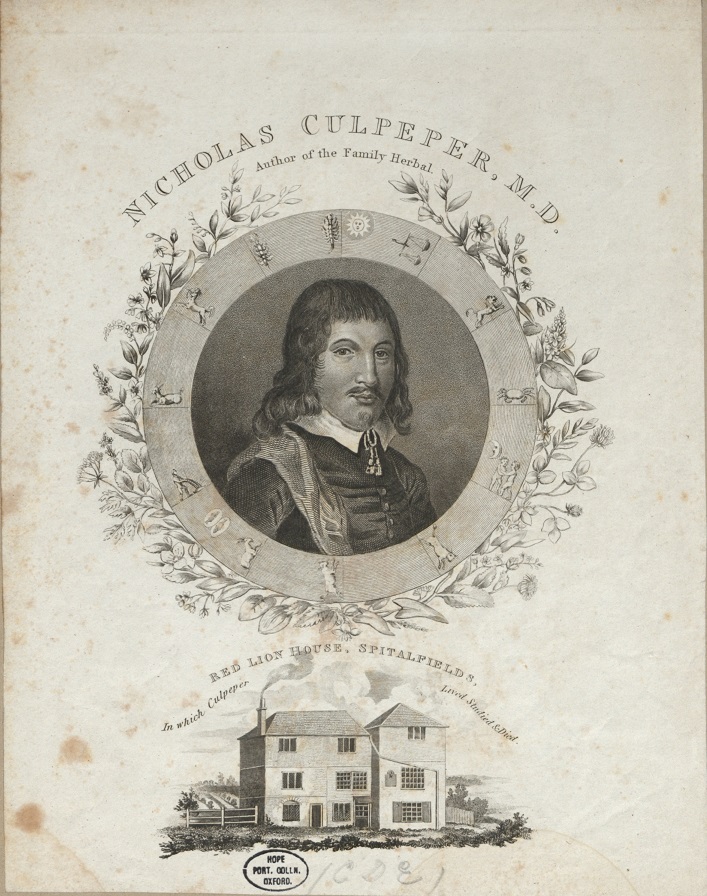

Print (Engraving) of Nicholas Culpeper, Inv. No.52753 [4]

Physiognomic (emerging from the writings of Giacomo della Patra) and humeric principles were used to emphasise a person’s character as ‘melancholic or choleric’. Natural philosophers are frequently depicted with instruments. Astrologers surrounded by zodiac symbols or calculating genitures and drawing up horoscopes. Collectors such as Ole Worm were often depicted in seventeenth century wunderkammer portraits as honourable figures surrounded by their collections. W. Elder’s engraving of the portrait of Theodore du Mayerne (Inv. No. 89142 [5]) depicts him pointing to a skull, to indicate his status as the king’s physician. The development of the camera obscura allowed for more realistic and finely detailed renderings of a subject and was increasingly used in the seventeenth century.

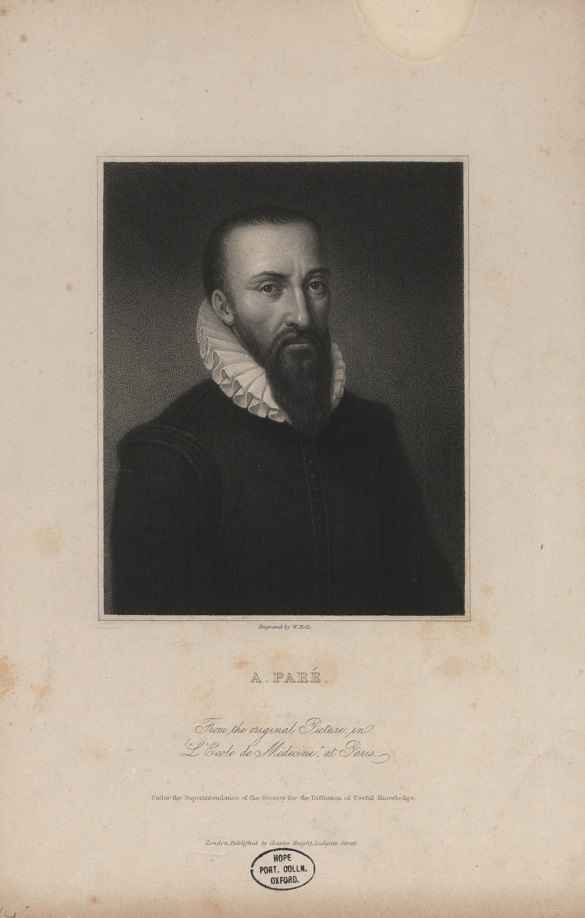

The use of portraits by James Granger to depict historical events in the Biographical History of England had a significant influence on the portrait in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century. A history of the sciences was depicted through the prints published by Charles Knight and paid for by the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. They comprise a mix of stipple and line engraving, often used in combination. W.T. Fry (1789–1843) was one of the first engravers to experiment with steel plates. This method was used for his printed portrait of the English astronomer Edmund Halley (Inv. No. 82823 [6]). The portrait of Ambroise Paré (Inv. No. 77792 [7]) was engraved by William Holl the Younger (1807–1871). Holl, from a family of engravers, made engravings of the Royal Family for most of his career. James Thomson was another portrait engraver who worked with Knight.

Print (Stipple Engraving) A. Paré, engraved by W. Holl, from the original picture in L’Ecole de Mediicine at Paris, published by Charles Knight, Ludgate Street, London, 19th century, Inv. No. 77792 [7]

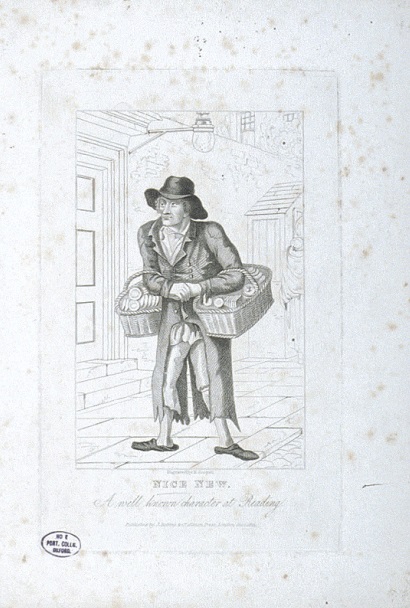

Print (Engraving) ‘Nice New / A Well Known Character at Reading’, engraved by R. Cooper, published by J. Robins, London, 1821, Inv. No. 25353 [8]

A caricature is a portrait that depicts madness and ugliness. The main examples in the prints collection can be found in James Gillray’s caricatures of eighteenth century natural philosophic and scientific society in London, and in the more gentle stipple engravings made by the freelance engraver Robert Cooper in the early nineteenth century. Cooper’s illustration of ‘Nice New’, an interesting character at Reading, was part The Book of Wonderful Characters : Memoirs and Anecdotes of Remarkable and Eccentric Persons in all ages and Countries by Henry Wilson and James Caulfield that depicted its subjects in the terms set by James Granger’s biographical arrangement of history.

In the nineteenth century, there was an ever greater search for accuracy and likeness, accompanying new photographic technologies and aspirations towards scientific objectivity. The development of lithography and photography further revolutionised the portrait.

Further reading: Ludmilla Jordanova, Defining features : scientific and medical portraits, 1660-2000 ( London : Reaktion in association with the National Portrait Gallery, 2000)