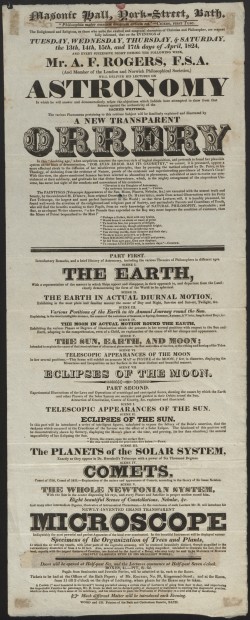

Print (Broadside) Advertisement for Astronomy Lecture Given by Mr A.F. Rogers at the Masonic Hall, Bath, Printed by Wood and Co. Bath, 1824. Inv 14458 [1]

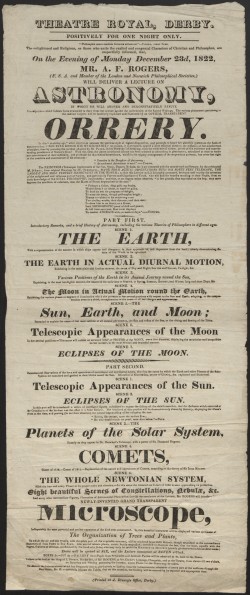

Print (Broadside) Advertisement for Astronomy Lecture Given by Mr A.F. Rogers at the Theatre Royal, Derby, Printed at J. Drewry’s Office, Derby, 1822. Inv 14454 [2]

The prints collection includes numerous lecture and exhibition notices in the form of posters and handbills giving details of the content, time and location of the events. Public lectures and exhibitions were particularly popular in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries thanks to an enlightenment enthusiasm for ‘rational amusement’ and their combination of education and entertainment. Audiences ranged from royalty and aristocracy to the more humble.

Lecture themes commonly focused on astronomy, mechanics, magnetism, hydrostatics, pneumatics, optics, electricity and chemistry. Astronomical lectures were particularly popular and the majority of our notices are for astronomical lectures. Astronomy appealed to a wide audience; anyone could take part by simply observing the moon and stars and most people had a rudimentary knowledge of the night sky.

Audiences were not restricted to those in the capital; our prints advertise locations such as Derby, Bath, Oxford, Edinburgh and Liverpool. Indeed by the 1760s itinerant scientific lecturing was in fashion – an example of a famous lecturer being Benjamin Martin [3] who transported scientific apparatus for demonstrations from town to town. However, London still dominated scientific life and many scientific societies, though national, were predominantly based in London.

Many of the lectures included the use of visual display, either through magic lantern slides, or working models and orreries. Lectures often had similar content and dealt with a summary of astronomical knowledge of the time, or with current astronomical phenomena, presented in a suitable manner for a lay audience. The lectures did not please everyone, and an 1875 article in the Saturday Review claimed that audiences were either split into those only attending because it was the fashion and those with good intentions but limited understanding. The article further criticized the lecture itself for being ‘invented’ to make it suitable for the public platform. The nameless critic criticized incompetent and amateur lecturers who host lectures with limited and inexpert knowledge. Nevertheless, the critic does admit that there are advantages to science being popular and fashionable and whatever the motivation for attending, large audiences were receptive to science. Indeed, a popular astronomical lecturer in the 1820s and 1830s, John Wallis, was obliged to add a second show at the Mechanics Institute as the demand was so great.

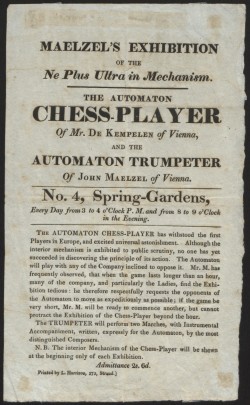

Print (Handbill) Advertising an Exhibition of Chess Automaton at the Spring Gardens, Printed by L. Harrison, London, 19th Century. Inv 13202 [4]

Some lectures were presented by those attempting to persuade audiences of the existence of God, and in the case of the lectures given by Mr A.F. Rogers in both Derby and Bath (in 1822 and 1824 respectively), combat ‘heathen’ Newtonianism.

Popular lectures were not the only way that a general public engaged with science and technological advancements. Alongside the growing popularity of books, journals, encyclopedias and lectures, exhibitions attracted much attention and enjoyment. The exhibition catered to the same interests as print culture; a desire to be educated and entertained.

Examples of advertisements for exhibitions in our collection range from mechanical novelties, new inventions, curious people and animals, to scientific instruments and give an insight into the dominant ideas of the time and prevailing ‘culture of exhibition’. The nature of exhibitions is to attract and maintain an audience and so advertisement notices can reveal much about the popular culture of the time. Exhibitions had the potential to reach a large audience whether to supplement or replace reading and education. The exhibition could also act as a class leveler – curiosity did not have class boundaries and the exhibition could provide one of a few social settings where boundaries could be merged. Indeed the English were famous for a widespread enthusiasm for exhibitions regardless of class.

The handbill advertisements in our collection demonstrate the broad range of exhibition topics from scientific instruments and technological innovations: a ‘chess automaton’ (Inv. 13202 [4]), ‘the smallest watch ever seen’ (Inv. No.13207 [5]), a demonstration of a perpetual motion machine (Inv. No.13200 [6]), ‘Handcock’s carriage for travelling without horses’ (Inv. No. 13203 [7]); to natural curiosities: the skeleton of a mammoth (Inv. No. 13199 [8]), an armadillo (Inv. No. 13950 [9]), and double-jointed ox (Inv. No. 13928 [10]); to a remarkable child arithmetician (Inv. No. 13209 [11]).