Laura Ashby chats with “Eccentricity” co-curator Tony Simcock

Laura: So Tony, what’s it all about, eccentricity?

Tony: D’you mean eccentricity or “Eccentricity”?

L: Take your pick.

T: Well Laura, eccentricity turns out to be a bit like “Eccentricity” – or vice versa – when you see it it’s obvious what it is, when you describe it it’s a bit less clear, when you try to define it it goes all mushy. It slips right through your fingers.

L: Try anyway.

T: I’ll tell you one characteristic, that keeps cropping up. You must have noticed how it keeps swinging between poignance and panto …

L: I have indeed. But you’d better explain what you mean anyway.

T: You laugh and then you cry. You’ve no sooner convinced yourself that something’s completely ridiculous than you realise it’s saved the world. It’s the very opposite, it’s undiculous.

L: You’re not allowed to make words up, by the way.

T: Take Joseph Wright for instance. We introduced him in an amusing way – must have been a practical joke, bringing this chap with a broad Yorkshire accent to teach philology at Oxford. And accepting him because he was a great pipe smoker. But before long we had a lump in the throat – at least I hope we did …

L: I couldn’t swallow for a fortnight.

T: Picturing a man who started his career aged 6 as a donkey boy in a quarry, rising to become an Oxford professor and one of the most eminent linguistic scholars of his day. We note how Jevons’s logical piano was ridiculed, and, like Babbage’s difference and analytical engines, was a complete failure … then we remind ourselves that they are the forerunners of the computer, which means that the men who thought of these ideas and were once figures of ridicule must now rank as founders of the modern world. We make mild fun of dear old Lewis Carroll’s system of logic and the idea that it can be worked out as an equation in algebra; but that’s part of what modern computers do do.

L: Dee-doo do dee-doo.

T: And ravenous old Buckland, with his panther pie and mouse in batter, was the geologist who founded the subject of ecology – the study of living things with reference to their environment – and pushed back the boundaries of creation beyond the old wisdom of 4004 BC, ready for Darwin to step in with millions of years of evolution. So. Are they geniuses or nutcases?

L: Or, are geniuses all a tad eccentric?

T: OR – is eccentricity necessary, like curiosity and memory and oxygen? Necessary to big-brained bipeds, necessary to human intellectual progress, and thus to evolution a million years back and to science in recent centuries.

L: Cool – this is getting …

T: I know, you thought you were interviewing Edna Everage and you got Jonathan Miller instead.

L: Who?

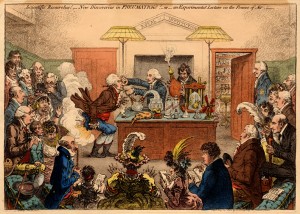

T: The whole exhibition’s been like that. And that’s what I mean. The moment you see how ridiculous something is, it turns serious. The moment you think you’ve spotted a bit of pure eccentricity, you realise there’s method in the madness. Take Daubeny’s monkeys …

L: No thanks.

T: Even though he was ridiculously short and bespectacled and obviously had a very squeaky voice, Daubeny had a serious philosophy that science or anyway science teaching or anyway science teaching in Oxford or anyway science teaching in Oxford colleges …

L: [the look says it all]

T: Or anyway science teaching at Magdalen College, should be comprehensive and broadly based; so although he was a chemist and botanist himself, he introduced physics and meteorology and zoology – that’s the monkeys – and astronomy and geology etc into his teaching. He installed a big telescope at the Botanic Garden – you’ll probably say he was looking for life on other PLANTS!

L: I was going to say, looking for plant-life in space.

T: Mmm, better leave the jokes to me then.

L: Arumph.

T: But monkeys in a cage are a lot funnier than telescopes …

L: Especially when they escape …

T: But you see Daubeny’s monkeys and telescope were doing the same thing – they were expanding the curriculum.

L: No, you’ll never make expanding the curriculum seem funny.

T: That’s it. And several of our lecturers have bravely tried to define eccentricity or an eccentric, and its place in society or in science. It’s a tough assignment. Brian Regal’s conclusion that science and the world NEEDS people who waste their lives in quest of the non-existent Abominable Snowman is sort of sad, perhaps, more than funny. For that’s the point where eccentricity evaporates, or slips through your fingers.

L: Like old Bigfoot himself.

T: And you know Laura, it’s been doing this throughout the exhibition. You think you see it, shadowyly, on the hillside – you focus in – and it’s gone. Puff! It’s a puff of snow blown off the horizon by a distant breeze.

L: So it gets us nowhere?

T: Ah but we never intended – I don’t think we did anyway – to raise a debate about the nature of BEING a scientist or of intellectual evolution or of scientific discovery. Yet there it was, a big hairy footprint in the snow, a profound debate about these things appears to exist. We didn’t really intend to make fun of our heroes and heroines. Yet there they were, as soon as our backs were turned, pulling funny faces at us …

L: Or farting.

T: Laughter’s extremely good for the brain by the way.

L: Save me a bottle.

T: And I’m sure we didn’t intend the exhibition to be about eccentricity.

L: What was it meant to be about then?

T: I’m glad you asked me that. Because there IS something that’s hardly been raised at all, something absolutely fundamental, and it’s got nothing or little to do with eccentricity, and almost – almost – tempts me to say that everyone’s missed the point. But I won’t say that …

L: Oh go on.

T: Because every point of view is valid, and indeed a characteristic of something’s worth is its depth – its capability of accommodating multiple levels of meaning or relevance. It’s only, well, for my part, I wish that more people who came around museums were interested in MUSEUMS … You’ll say, what an odd thing to say …

L: What an odd thing to say, Tony!

T: After visitors have poured into our lovely museum and enjoyed and learned from the collections they’ve seen displayed there. But to me the exhibition “Eccentricity” is about the scope and parameters of museum collections. And there’s a big debate there. And we haven’t had it, and we can’t have it now …

L: Oh let’s …

T: No, it’s too big and boring. And d’you know something – it’s probably a good job nobody’s thought of it. Because it’s a debate that could go against us. Nowadays, museums have to write mission statements and collecting policies and even disposal policies. And donors have to sign legal transfer documents. And safety officers have to run geiger-counters over things.

L: [raised eyebrows]

T: No, honestly, Soddy’s suitcase was geiger-countered before we put it on display.

L: Get to the point.

T: Hardly anything in the exhibition would be acquired today under today’s collecting policies. Several things came quite accidentally. Burdon Sanderson’s wallet was swept up with miscellanous stuff from the floor of Haldane’s laboratory and bunged in a tea-chest to be sorted out 20 years later. One of the things in the tea-chest was a stale sandwich, which I threw away.

L: Yes, we’ve got that joke somewhere else.

T: It’s no joke Laura. Neither our collecting policy nor our disposal policy says anything about sandwiches or suitcases. Did you know we’ve got King Charles II’s address book?

L: Throw it away!

T: And the world’s oldest collection of birds’ eggs.

L: So why aren’t they in the exhibition?

T: And a melted tile from Hiroshima …

L: Cool.

T: From panto to poignance. I wonder whether there shouldn’t be a regular, changing exhibit of an unexpected offbeat treasure from the collections. Because you see I think – and I’m not sure eccentricity was the best word for it – the exhibition was about …

L: The exhibition called “Eccentricity”.

T: Yes. I sort of suspect the exhibition was about the nature of a museum collection. The debate – no, we’ve decided it’s best not to encourage a debate – the generality, the paradigm, the background noise, the footprint in the snow isn’t to do with the eccentricity of historical characters, neither eccentric like nutty nor eccentric like outside the mainstream. It’s to do with eccentricity in serious museum collections. The frilly peripheries of the collections. The crimping machines. The Chinese typewriters. The items in the collection that are way off centre, that don’t conform – nonconformity would have been a better word …

L: That would have pulled the crowds.

T: The things in the collection that don’t conform to any conceivable definition of what we’re about or what we collect AND YET ARE TREASURES EVEN SO. Put that in capital letters.

L: I shall.

T: Poignant treasures. Revealing treasures. Entertaining treasures. Informative treasures. Important treasures even so.

L: Priceless.

T: Yes, get that word in somehow too. But they’re waifs, they’re all orphans and foundlings, they’re the most fragile parts of the collection. Fragile in terms of the probability of them ever having been saved in a museum at all. Several of the objects in the exhibition we’ve had for decades, but I’ve catalogued them only recently – elevating them to the status of real museum objects. Who was it who said ‘museum objects aren’t just what they are, they are what they’ve become’?

L: You I think.

T: Well there you are then. Soddy’s suitcase is one – an object I elevated from statuslessness I mean – Miss Willmott’s empty lantern-slide box with her name plaque another. Wonderful paradox there – Soddy’s suitcase had no identity as a museum object in its own right because it was just a container, a cardboard box manquee …

L: Can we say substitute?

T: Just a container – it was full of lantern slides. Miss Willmott’s lantern-slide box had no identity as a museum object in its own right because it was empty, it had no lantern slides in it. I like that paradox.

L: Worthless if you’re full of lantern slides and worthless if you’re empty.

T: D’you see what I mean though?

L: Not the faintest.

T: It’s the museum world turned upside-down. The exhibition is SUBVERSIVE. It’s nonconformist. It’s an exhibition curated by levellers. It’s revolutionary. The collection’s most worthless, improbable, unregarded, off-beam, accidental, ex—I nearly said eccentric!

L: Not allowed, miss a turn.

T: Most peripheral most waif-like objects, dusted down and displayed as a collection of priceless fascinating treasures. And it works!

L: Worked.

T: It worked. They are! They’re priceless.

L: They are indeed. Well I’m sorry we’ve run out of time now, so thanks a lot Tony.

T: Thankyou Laura. Byebye.

L: Byeee … Now he’s gone I should just add that Tony Simcock’s opinions are not necessarily the opinions or policies of the Museum of the History of Science or of Oxford University. To be honest – I suspect he’s a little eccentric …